Where Do Images of Art Go Once They Go Online? A Reverse Image Lookup Study to Assess the Dissemination of Digitized Cultural Heritage

Isabella Kirton, UK, Melissa Terras, UK

Abstract

Once digital images of cultural and heritage material are digitized and placed online, how can we tell if they are copied, disseminated, and reused? This paper explores Reverse Image Lookup (RIL) technologies – usually used to identify unlicensed reuse of commercial photography - to help in assessing the impact of digitized content. We report on a pilot study which tracked a sample of images from The National Gallery, London, to establish where they were reused on other webpages. In doing so, we assessed the current methods available for applying RIL, establishing how useful it can be to the cultural and heritage sectors.

RIL technologies are those which allow you to track and trace image reuse online. We choose two samples of paintings from the National Gallery: all paintings held in Room 34 entitled ‘Great Britain 1750-1850’, containing 26 paintings by 9 artists, just over 1% of their total number holdings (National Gallery, n.d.). We also created a random sample of 6 paintings, from different artistic periods and of varying levels of fame. We analysed the dissemination of these images using TinEye and Google Image Search, using Content Analysis (White and Marsh 2006) to discover the contexts for image reuse. We then triangulated findings using web access statistics from the National Gallery’s Google Analytics account, and from the commercial ISP analysis firm Hitwise. Our results provides a qualitative analysis of types of image reuse.

This study has allowed us to establish what motivates image reuse in a digital environment. We recommend a framework for data collection that could be used by other organisations. However, we also show that there are limitations to the information that can be gleaned from a study of this kind, due to the problematic implementation of the RIL tools which were not designed for this sector.

Keywords: Digitization, Impact, dissemination, evaluation, Reverse Image Lookup

1. Introduction

Once digital images of cultural and heritage material are digitized and placed online, how can we tell if they are copied, disseminated, and reused? This paper explores Reverse Image Lookup (RIL) technologies—usually used to identify unlicensed reuse of commercial photography—to help in assessing the impact of digitized content. We report on a pilot study that tracked a sample of images from The National Gallery, London, to establish where they were reused on other Web pages. In doing so, we assessed the current methods available for applying RIL, establishing how useful it can be to the cultural and heritage sectors.

RIL technologies allow you to track and trace image reuse online. The main commercial service, TinEye, available since 2008, finds “exact and altered copies of the image you submit, including those that have been cropped, colour adjusted, resized, heavily edited or slightly rotated” (TinEye, n.d.). Since 2007, Google Images search has also provided a free service that can find similar images across the Internet, allowing search by image URL since 2011. Can these tools provide a useful method for tracking reuse of images of paintings once they are placed online? Kousha, Thelwall, and Rezaie (2010) previously published a pioneering study that assessed the “image reuse value” of academic scientific images and provides a useful framework. Prior studies in the cultural and heritage sector have looked at the image requirements of users (Cunningham, Bainbridge, & Masoodian, 2004; Cunningham & Masoodian, 2006), the kind of terms people use when searching for art historical images (Chen, 2000), how people use images in their research (McCay-Peet & Toms, 2009), and more general research on how people find digital images online (Jansen, 2008; Westman, 2009). Nonetheless, we believe ours is the first systematic study to use RIL to look at digitized heritage content to ascertain reuse of image content.

We chose two samples of paintings from the National Gallery: all paintings held in Room 34 entitled “Great Britain 1750-1850,” containing twenty-six paintings by nine artists—just over 1 percent of their total number holdings (National Gallery, n.d.). We also created a sample of six National Gallery paintings, chosen from different artistic periods and of varying levels of fame. We analysed the dissemination of these images using TinEye and Google Images search, and using content analysis (Domas White & Marsh, 2006) to discover the contexts for image reuse. Our content analysis provided a qualitative analysis of types of image reuse, such as commercial art publishers, blogs, reviews, tourism, image collections, encyclopaedias, other museum websites, DVD cover images, and beyond. We demonstrated that type and volume of image reuse are both subject and artist specific.

We then triangulated findings using Web access statistics from the National Gallery’s Google Analytics account, and from the commercial ISP analysis firm Hitwise. Our results show that the most popular paintings (by access) are the ones most commonly reused elsewhere, but we also uncover a feedback loop that proves dissemination of images elsewhere online provides direct traffic back to the host institutions’ websites.

This study has allowed us to establish what motivates image reuse in a digital environment. We recommend a framework for data collection that could be used by other organisations. However, we also show that there are limitations to the information that can be gleaned from a study of this kind, due to the problematic implementation of the RIL tools which were not designed for this sector.

2. Method

We chose two samples of paintings from the National Gallery, aiming to give us a spread of very famous to lesser-known works from a major gallery to test the efficacy of RIL technologies across a set of differing images. The first sample contains all the paintings held in Room 34, “Great Britain 1750-1850,” which contains twenty-six paintings by nine artists (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/visiting/floorplans/level-2/room-34). This accounts for just over 1 percent of the total number of paintings in the National Gallery (Cupitt & Saunders, 2002, p. 523) and includes three paintings on the National Gallery’s “30 highlight paintings” list. (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/explore-the-paintings/30-highlight-paintings/)

We have also created a random sample of six paintings from across the gallery, which are from different artistic periods and have varying levels of fame: Sunflowers by Vincent van Gogh, The Arnolfini Portrait by Jan Van Eyck, Whistlejacket by George Stubbs, Doge Leonardo Loredan by Giovanni Bellini Doge, The Lower Falls of the Labrofoss by Johan Christian Dahl, and A Still Life of Flowers in a Wan-Li Vase by Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder. This allowed us to analyze the dynamics of tracking paintings with different values and popularity in their analogue form. To collect the majority of our data, we used the image search engine TinEye (www.tineye.com). We performed searches by placing the URL of an image from the National Gallery website into the search engine, which searched over 2 billion images in the TinEye database to return any matches of this exact image elsewhere online. The results from any TinEye search are valid for 72 hours, and searches on all our sample paintings were completed within the 72-hour period to collect the most accurate data we could, given all information recorded is from one specific time frame.

Figure 1. The TinEye interface. This shot shows the 316 reuse results obtained for the image of The Fighting Temeraire by Joseph Mallord William Turner on the National Gallery’s website.

We then performed content analysis on every URL returned by the search to collect information on how the image is used (similar to the methods used by Kousha, Thelwall, and Rezaie (2010), although we had to determine our own classification for this study). Content analysis is a process that allows quantitative classification of information to allow comparisons and deductions to be made (Domas White & Marsh, 2006). We created a list of categories to record, including the context the image was reused in, and noted whether the original source for the image, National Gallery, and artist names was mentioned, and the URL where the image can be found elsewhere online. The categories that emerged from our analysis indicate the type of websites that reuse images: Art – Commercial, Art – Education, Art – Review, Article, Artist Biography, Blog, Book cover image, CD cover image, Collection of Images, Commercial Website, DVD Cover image, eBook illustration, Encyclopedia, Forum, Free download site, Museum Website, Online Game, Personal Website, Podcast image, School website, Social Media Profile, Society Website, Stock Photography, Travel website, Vote for Greatest Painting, Website design tutorial, and Unknown.

We used Google Translate to help us interpret how the images are being used on non-English-speaking websites. We also created a framework for processing and checking our data upon collection. Occasionally the same URL will appear duplicated: for example we collected 288 results for the image of Rain, Steam and Speed by Joseph Mallord William Turner but found 25 duplicate URLs within this set (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/joseph-mallord-william-turner-rain-steam-and-speed-the-great-western-railway). We removed all duplicate URLs from our results but kept multiple pages from one website in our results if an image was reused in different places on one website. The resulting collected data allowed us to understand and quantify the contexts in which the disseminated images are used.

We have created a clear framework for both data collection and processing, which has allowed us to obtain useful and detailed information from our searches, although the results we collect are based on TinEye’s limitations: our searches reveal the dissemination of images merely from the sizeable subset of pages it has indexed rather than the whole Internet. To assess the results generated from TinEye, we undertook the same analysis with three of the most reused paintings: Whistlejacket by George Stubbs (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/george-stubbs-whistlejacket), Constable’s Stratford Mill (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/john-constable-stratford-mill), and the Evening Star by J. M. W. Turner (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/joseph-mallord-william-turner-the-evening-star). This time we used Google Images search as the means to find copies of images online; the differences in the searches returned highlighted further issues with the tools currently available to undertake this type of research.

We then analysed web user statistics of the National Gallery’s pages to see if we could identify any trends that contribute to why and how these images have been disseminated, using information from two different sources: a Hitwise report from Experian Marketing (http://www.experian.com/marketing-services/about.html?intcmp=ems_enav_abus_lrn_abut#hitwise), which gave access statistics for the paintings on our second sample list for a three-month period, based on commercial Internet service provider data; and the National Gallery’s Google Analytics account, which gave further information about traffic to the National Gallery’s website.

3. Results

Content Analysis

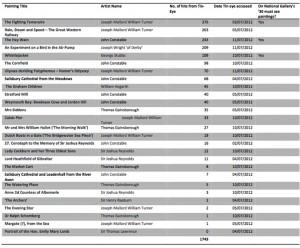

In total, we analysed the reuse of thirty-two paintings, investigating and classifying over 3,000 reuse cases. There were a total of 1,743 reuses of images of the twenty-six paintings in Room 34 of the National Gallery: the mean number of reuse instances per painting was 65, whilst the median number of results was 27, showing that images of certain paintings were disseminated much more widely than others.

Table 1: Quantity of image reuse for the twenty-six paintings in Room 34 of the National Gallery, ascertained by number of results generated from TinEye

The manifold nature of why an image may be reused becomes clear when looking at the most commonly reused image: that of The Fighting Temeraire (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/joseph-mallord-william-turner-the-fighting-temeraire). This painting is exemplary of Turner’s work and is therefore frequently chosen to represent the artist in either a blog entry or an article as an accompaniment to a general discussion of Turner (e.g., Intelliblog, 2009). Furthermore, the painting’s historical British subject matter means that the image is easily associated with British Naval and Imperial history, so is frequently used as an illustration for the Battle of Trafalgar (e.g., British Battles, 2012). Finally, as the winner of the vote for the nation’s greatest painting in September 2005, it has received wide publicity (BBC Radio 4, 2005). Therefore it is probable that The Fighting Temeraire has generated the most image reuse out of the paintings in Room 34 because of the prowess of the artist, the artistic technique demonstrated, its subject matter, and its prior publicity.

Our content analysis determined in what context images of the twenty-six paintings had been reused on the Web pages returned by the TinEye searches.

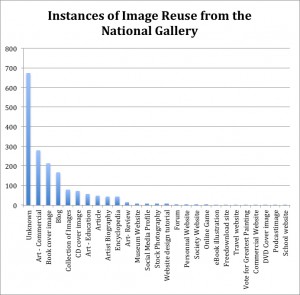

Figure 2: Type of website hosting an image reused from Room 34 of the National Gallery, taken from their website

A large percentage (39 percent) of results returned for each image fell into the category labeled “unknown,” which covers URLs no longer available, pages we were denied access to, and pages where the image was not actually visible and therefore we could not confidently determine in what context it was being used. We can infer from this that TinEye crawled many of these pages some time ago, as the content has been modified or removed, highlighting the impermanent nature of Web pages and the difficulties faced in a study such as this dealing with constantly changing, dated content.

Across Room 34, the most frequent context the images were found in (after “unknown”) was the “art – commercial” category (16 percent), which covers art posters, reproduction paintings, and other products such as mugs and t-shirts featuring the image. Book cover images and CD cover images make up 12 percent and 4 percent of the total results for Room 34. However, we do see the percentage of “art – commercial” results per painting vary greatly across the paintings from Room 34: from 0 percent to 50 percent. Images of paintings that have complex subject matter—such as Joseph Wright of Derby’s An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, which depicts a travelling scientist performing an experiment on a bird surrounded by a large audience (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/joseph-wright-of-derby-an-experiment-on-a-bird-in-the-air-pump)—are more frequently reused. This painting is also very frequently used on book cover images, blogs, and articles, and we have found images of book covers used not just on commercial websites that are selling copies of the book but also within blog entries. The subject matter of this painting seems to provide a number of points for reuse on websites regarding the enlightenment and the history of science and thought. This indicates that subject matter and theme provide a core motivation for an image’s reuse on the Internet.

Reuse of images on blogs was popular (9 percent of overall reuse): images of eighteen of the twenty-six paintings in Room 34 feature in a blog posting. They were commonly used on blogs regarding visits to the National Gallery but also in more abstract cases, such as to accompany a poem or piece of creative writing. With image reuse on blogs, people take images and contextualize them in their own way, highlighting that digitized content has the ability to remove itself from the traditional museum based narrative attached to its analogue counterpart (Cameron & Robinson, 2007). This is also apparent in the “collection of images” category, where individuals had put together their own collection of unique images to reflect a chosen theme in a Web gallery setting. Other relatively popular categories related to online resources provided art historical information, such as articles, artist biographies, and encyclopedias. The results returned from this search found only a few examples of remixed images (an important part of meme culture; see Lessig, 2009). The Haywain, for example, was remixed in various ways (http://www.b3ta.com/board/10279143) as part of an “Update Art” Challenge posted on the B3ta remix forum (http://www.b3ta.com/challenge/national_gallery/), as were images of the Fighting Temeraire (e.g., http://www.b3ta.com/board/9971748). A further avenue of study for future research would be to look more closely at the relationship of remixed art images, and their original sources.

Four-fifths (80 percent) of the reuse results do not mention the National Gallery; however, 55 percent of the overall results for Room 34 did mention the artist in some capacity, indicating that artist is more important than source to those reusing images, or that museum websites could make it easier for people to cite and reuse content effectively. Only 16 percent of the results correctly cited the original source of the image.

TinEye versus Google Images Search

We directly compared the results from TinEye with Google Images search, which allows you to search for copies of an exact image by entering the image’s URL in the Google search bar. We did this by comparing the results from three images from Room 34 to ascertain how different the results from the two different tools were (Google and TinEye only make available limited information about how their respective technologies search and retrieve images publicly). Google Images returns a significantly larger number of results for each search than TinEye does: for Whistlejacket by Stubbs, the TinEye search returned 109 results whilst Google Images search returned 271. This is directly related to the size of their image database: on May 24, 2012, TinEye stated its database contained 2,157,168,890 images (TinEye, 2012), whilst by 2010 Google had already indexed “over 10 billion images” (Google Official Blog, 2010). Google’s database appears to be more up to date than TinEye’s: only 5 percent of pages were unclassifiable and labeled “unknown” versus TinEye’s 39 percent. There was also little crossover between the results found using Google and TinEye: for Whistlejacket, out of the 109 results retrieved by TinEye and the 271 results retrieved by Google, only 6 URLs were retrieved by both. It also became obvious that the different way they processed and presented the results affected the ease with which we could utilize the tools. Google Images constantly readjusts its search results as you move through the pages of found images, omitting various similar pages, but duplicating other results, making it difficult to feel fully in control of the data collection process and making the results from Google almost unusable. In terms of transparency, TinEye is superior, as it presents its search results in a much more straightforward way that gives more confidence in it as a tool: however, the difference in URLs found between the two stress that we have to be aware that any such use of RIL tools looks at a small sample of online content, not trawling the whole of the Internet for image reuse. This can undermine the use of these tools for anything but a guide as to how to understand image reuse.

Triangulating with Web Usage Statistics

So far we have considered how features and trends of our images’ analogue counterparts have affected the extent to which they have been disseminated in a digital environment: can we use Web statistics to identify trends that contribute to why and how these images have been disseminated? We were given access to the National Gallery’s Google Analytics account by their Web team, and to a report produced by Hitwise, which produced three months of ISP data regarding access to the National Gallery’s website, to correlate Web visits to the painting’s individual pages with reuse statistics of the images.

The most visited Web pages correlated with the most widely disseminated images. This is backed up by the figures generated from both Hitwise and Google Analytics. Paintings such as van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jan-van-eyck-the-arnolfini-portrait), which was reused on 704 websites according to TinEye, and Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/vincent-van-gogh-sunflowers), reused on 620 websites, were amongst the most frequently visited painting pages on the National Gallery’s website, with visitors often starting their use of the National Gallery’s website on those pages directly from a search engine. Less-famous images included in our sample, such as Dahl’s The Lower Falls of the Labrofoss (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/johan-christian-dahl-the-lower-falls-of-the-labrofoss) returned no reuse results from our TinEye searches, and received the lowest website visitor traffic out of all the paintings from our sample. There is a clear correlation across all the paintings: those with the highest Web traffic are those whose images are most reused online.

This may seem obvious (popular or important paintings are looked at online, and their images reused elsewhere, more than unpopular paintings), but more interestingly we used Google Analytics to track the Web page that visitors to painting pages on the National Gallery website entered from, providing information about the digital context visits to these pages were made within. We cross-referenced the websites listed by the Google Analytics report with the URLs in our TinEye search results in order to assess whether there was a continued dialogue between the disseminated images and the National Gallery website.

We found that of the 151 websites from which people accessed the Sunflowers Web page, 7 visits were from websites on which we located versions of the image in our TinEye search within a period of a month. For The Arnolfini Portrait, out of 129 websites that sent visitors to the National Gallery’s Sunflowers web page, 8 had versions of the artwork’s image on the source page. There is therefore a small but significant feedback loop: reuse of images of content elsewhere directs users back to the National Gallery’s website. This should be noted by other institutions considering allowing their data to be reused elsewhere, as reuse of content can drive traffic. This result is also backed up by data from the Hitwise report that finds the same sites provide a click stream to the painting pages on the National Gallery website. Hitwise’s data also shows that traffic to the Sunflowers page is generated by reuse of the image on Wikipedia, the Vincent Van Gogh Gallery (vangoghgallery.com), and VisitLondon.com (visitlondon.com).

Unsurprisingly, the pages that direct traffic to the National Gallery’s website are those few that contextualize the images by referencing the National Gallery. These copied and disseminated images do not not only remain within a framework of discussion centered on the National Gallery but also actively draw people back to the gallery’s website and therefore the museum narrative more generally. Image reuse elsewhere (such as on blogs and image collections, which we showed was a major source of image reuse) promotes a visit to the source of the image, which is perhaps the most useful of our research findings in this process. It also points for the need to consider usage licenses, and mechanisms for citation, when placing digitized content online: the freer the license, and the more reuse of digital content, the more the original institution will benefit. (This effect is also discussed in the Tate’s Online Strategy document (Stack, 2010))

4. Discussion

This study has explored how RIL search engines can be utilized to track and assess how digitized cultural heritage images are disseminated across the Internet. In order to draw conclusions about how useful this type of study is, we have to assess both the process undertaken to collect the data and the value of the information we have retrieved.

First, we must acknowledge the time necessary for data collection and whether that is a worthwhile investment: it took fifteen days of solid data collection to gain the results for our thirty-two searches with TinEye and three additional searches with Google Images search. This is not a quick-and-easy method for gaining data on the impact of a large volume of digitized images and therefore may be better suited to providing information about targeted and well-known parts of a collection. Furthermore, our sample only accounts for 1 percent of the National Gallery’s collection, which is relatively small compared to other institutions’, and it would be costly and time consuming to analyse a whole collection in this manner. The National Gallery’s paintings are amongst the most famous in the world, and we doubt that images of lesser-known collections would yield enough results to justify this type of systematic study; however, this is a freely available tool and therefore something cultural heritage institutions could use periodically to see how their images had been reused.

The ease at which information could be gathered was affected by the tools’ own limitations. Neither was designed with research of this kind in mind (more commonly being used to track one image of stock photography), and therefore the way they choose to filter and present their search results acted as a barrier to collecting clear and reliable data. The largest issue encountered was a lack of information available about how these search engines were trawling and collecting information; the out-of-date TinEye searches highlighted that we did not fully understand the data the tool was using. If the tools were more transparent about how they collect their information, they could be more confidently used by cultural heritage institutions that want to measure the impact made by their own digitized content. As they stand, they are commercial tools without any imperative to design a front end for the GLAM sector for this type of use.

This investment in data collection time is only justified if the framework created to analyse the content of the pages actually yields useful information. To some extent it can be argued that most of the information we collated states the obvious, although the process of content analysis allowed us contextual information to discuss type of image reuse. We were able to use our data to support a number of theories about how digitized cultural heritage material can be used either to interact with a traditional museum narrative or subvert it, highlighted by our ideas about how the subject matter of the paintings in the National Gallery collection affected how and why they were disseminated. We also provided quantitative evidence that image reuse draws people back towards the National Gallery. This is quantifiable information that could be used by cultural heritage institutions to justify the investment in digital materials and in making resources available to others for reuse. Scope for future research remains in ascertaining if images are altered in their reuse (and how that may be tracked), the effect that would have on visits back to an institution’s page, and if the availability of higher-resolution images would affect the nature and frequency of image reuse.

5. Conclusion

Reverse Image Lookup remains of interest to those producing online digital content in the cultural and heritage sector, and the use of the freely available tools to track image reuse can provide useful information to institutions. Nonetheless, we recommend that anyone who undertakes a study using these tools takes care when creating a framework for collecting information and directs their research questions accordingly.

This study has highlighted how little information we have on how digitized images of cultural content are reused in the Web environment, and more importantly the extent to which we lack a frame work for analysing this type of information. Furthermore, it has shown how little we know about the currently available tools, urging more transparency in their methods so that they are useful when looking at reuse of a range of material, rather than just tracking copyright infringement.

Our study has served to highlight that more needs to be done to consider how we can assess the motivations for the recontextualization of disseminated digital material in a Web environment. This is an important issue that feeds directly into bigger questions about impact and value facing the cultural and heritage sector at the moment. Ascertaining how digitized content is reused, and the impact this has on the original source, can tell us about user needs and behavior, and guide institutional policy on issues such as open access and image use permissions, encouraging better use of digitized content and better return on the investment required to undertake digitisation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Charlotte Sexton, Melissa Naylor, and Matt Terrington from the National Gallery, and Mike Tovell from Hitwise. We are not formally associated with either of these organisations.

References

BBC Radio 4. (2005). “The greatest painting in Britain vote.” BBC Radio 4 Today. Consulted March 5, 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/today/vote/greatestpainting/winner.shtml

British Battles. (2012). The Battle of Trafalgar. Consulted March 5, 2013. http://www.britishbattles.com/waterloo/battle-trafalgar.htm

Cameron, F., & H. Robinson. (2007). “Digital knowledgescapes: Cultural, theoretical, practical, and usage issues facing museum collection databases in a digital epoch.” In F. Cameron & S. Kenderdine (Eds.), Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse, 173. London: The MIT Press.

Chen, H. L. (2000). “An analysis of image queries in the field of art history.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 52(3), 260–273.

Cunningham, S. J., & M. Masoodian. (2006, June). Looking for a picture: an analysis of everyday image information searching. In Digital Libraries, 2006. JCDL’06. Proceedings of the 6th ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Conference on (pp. 198–199). IEEE.

Cunningham, S. J., D. Bainbridge, & M. Masoodian. (2004, June). “How people describe their image information needs: A grounded theory analysis of visual arts queries.” In Digital Libraries, 2004. Proceedings of the 2004 Joint ACM/IEEE Conference on (pp. 47–48). IEEE.

Cupitt, J., & D. Saunders. (2002). “Accurate colour images from expensive luxury to essential resource.” In 9th Congress of International Colour Association, Proceedings of SPIE, Vol. 4421, 523–527.

Domas White, M., & E. E. Marsh. (2006). “Content analysis: A flexible methodology.” Library Trends 55(1), 23–24.

Google. (2010, July 20). “Ooh! Ahh! Google Images presents a nicer way to surf the visual web.” Google Official Blog. Consulted March 5, 2013. http://googleblog.blogspot.co.uk/2010/07/ooh-ahh-google-images-presents-nicer.html

Intelliblog. (2009, July 12). “ART SUNDAY AND – TURNER AND THE END OF AN ERA.” Posted by Nicholas V. Consulted. http://nicholasjv.blogspot.co.uk/2009/07/art-sunday-turner-and-end-of-era.html

Jansen, B. J. (2008). “Searching for digital images on the web.” Journal of Documentation 64(1), 81–101.

Kousha, K., M. Thelwall, & S. Rezaie. (2010). “Can the impact of scholarly images be assessed online? An exploratory study using image identification technology.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 61(9), 1734.

Lessig, L. (2009). Remix: Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. Penguin Press.

McCay‐Peet, L., & E. Toms. (2009). “Image use within the work task model: Images as information and illustration.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60(12), 2416–2429.

National Gallery. (n.d.). “Room 34.” Consulted February 12, 2012. http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/visiting/floorplans/level-2/room-34

Stack, J. (2010, April 1). Tate Online Strategy 2010–2012. Consulted March 5, 2013. http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/tate-online-strategy-2010-12

TinEye. (n.d.). “Frequently asked questions.” Consulted. http://www.tineye.com/faq

TinEye. (2012). “TinEye release info and updates.” Consulted March 5, 2013. http://www.tineye.com/updates?year=2012

Westman, S. (2009). “Image users’ needs and searching behaviour.” In A. Goker & J. Davies (Eds.). Information retrieval: Searching in the 21st century, 63–84. Chichester: Wiley.

Cite as:

I. Kirton and M. Terras, Where Do Images of Art Go Once They Go Online? A Reverse Image Lookup Study to Assess the Dissemination of Digitized Cultural Heritage. In Museums and the Web 2013, N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). Silver Spring, MD: Museums and the Web. Published March 7, 2013. Consulted .

https://mw2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/where-do-images-of-art-go-once-they-go-online-a-reverse-image-lookup-study-to-assess-the-dissemination-of-digitized-cultural-heritage/