Digital Humanities and Crowdsourcing: An Exploration

Laura Carletti, UK, Derek McAuley, UK, Dominic Price, UK, Gabriella Giannachi, UK, Steve Benford, UK

Abstract

‘Crowdsourcing’ is a recent and evolving phenomenon, and the term has been broadly adopted to define different shades of public participation and contribution. Cultural institutions are progressively exploring crowdsourcing, and projects’ related research is increasing. Nonetheless, few studies in the digital humanities have investigated crowdsourcing as a whole. The aim of this paper is to shed light on crowdsourcing practices in the digital humanities, thus providing insights to design new paths of collaboration between cultural organisations and their audiences. A web survey was carried out on 36 crowdsourcing projects promoted by galleries, libraries, archives, museums, and education institutions. A variety of practices emerged from the research. Even though, it seems that there is no ‘one-solution-fits-all’ for crowdsourcing in the cultural domain, few reflections are presented to support the development of crowdsourcing initiatives.

Keywords: Crowdsourcing, Digital Humanities, Public Participation

1. Introduction

The term “crowdsourcing” is increasingly used to define online projects entailing the active contribution of an undefined public. But what does that notion mean? And what is crowdsourcing in the digital humanities?

Howe (2006), who coined the term, defines it as:

the act of a company or institution taking a function once performed by employees and outsourcing it to an undefined (and generally large) network of people in the form of an open call. This can take the form of peer-production (when the job is performed collaboratively), but is also often undertaken by sole individuals.

Crowdsourcing is an evolving phenomenon, and an exhaustive definition has yet to be identified. As newly shown in research, forty original definitions were found in thirty-two articles published between 2006 and 2011 (Estelles-Arolas & Gonzalez-Ladron-de-Guevara, 2012). The term certainly derives from business to identify the process of outsourcing part of an activity to an external provider, but it is currently used to identify a wide array of initiatives, both commercial (e.g., Amazon Mechanical Turk) and non-commercial (e.g., Wikipedia).

Being a recent paradigm, crowdsourcing is still debated. For instance, Wikipedia is commonly cited as an exemplar of crowdsourcing, despite the sceptical considerations of Jimmy Wales, one of its cofounders, who considers crowdsourcing just a business model to get the public doing work cheaply or for free.

Whether critical issues may arise in the profit sector, the perspective seems quite different in the public and non-profit sectors, where volunteering has a long and consolidated tradition, and unpaid work is done for a common good.

Cultural institutions are progressively exploring crowdsourcing, and projects-related research is increasing. Nonetheless, little has been written more generally about crowdsourcing practices in the digital humanities. The aim of this study is to explore crowdsourcing initiatives promoted by galleries, libraries, archives, museums, and education institutions, and to identify emerging practices.

2. Methodology

Initially, the literature on crowdsourcing was reviewed to gather documentation on projects, as well as to determine whether the crowdsourcing phenomenon had been researched within digital humanities. A first observation is that although there is a growing body of literature on crowdsourcing-specific projects, few studies in the digital humanities have investigated crowdsourcing as a whole (Holley, 2010; Oomen and Aroyo, 2011)

Recent research, as mentioned, has found forty original definitions of crowdsourcing. (Estelles-Arolas & Gonzalez-Ladron-de-Guevara, 2012) From that study, a comprehensive definition was proposed: “Crowdsourcing is a type of participative online activity in which an individual, an institution, a non-profit organization, or company proposes to a group of individuals of varying knowledge, heterogeneity, and number, via a flexible open call, the voluntary undertaking of a task.”

This definition was adopted in this study to identify and select crowdsourcing initiatives undertaken by galleries, libraries, archives, museums, and education institutions. Through the literature review and through circular Web links (e.g., Wikipedia list of crowdsourcing projects), a set of initiatives were identified: they were recognized as crowdsourcing practices only when the public was asked to perform a task (e.g., tagging, correcting) and to actively contribute to the project (some of the initiatives were explicitly defined as crowdsourcing projects; others were not). Thirty-six initiatives were selected and further analysed. Data were collected between March and June 2012, mainly through the projects’ websites, but also through other sources (papers).

Explorations of the websites were carried out; “field notes” and screenshots were taken. Data retrieved for each project were summarized into a synoptic table with nine columns (e.g., crowdsourcing task, type of digital artefact, number of contributors). The initiatives were analysed in terms of purpose, type of contribution (e.g., tagging, co-curation), number of and relation with contributors, results displayed (e.g., number of contributions), and timeline (e.g., duration). The findings on emerging practices are exposed below in terms of crowdsourced task and “crowd.”

3. Findings

Classification of crowdsourced tasks

Crowdsourcing is a relatively recent concept (Howe, 2006) that encompasses many practices. Taxonomies have been proposed in different areas, although very little has been written about crowdsourcing in the cultural domain. Oomen and Aroyo (2011) suggest a great potential for integrating crowdsourcing into the standard workflow of cultural institutions, and propose a classification of crowdsourcing linked to standard activities carried out by heritage organisations. They refer to the five-stage Digital Content Life Cycle model from the National Library of New Zealand (creating, describing, managing, discovering, using and reusing), and define different types of crowdsourcing for the five stages (Table 1).

Table 1. Classification of Crowdsourcing Initiatives (Oomen and Aroyo, 2011)

| Crowdsourcing Type | Short Definition |

| Correction and Transcription | Inviting users to correct and/or transcribe outputs of digitisation processes |

| Contextualisation | Adding contextual knowledge to objects, e.g. by telling stories or writing articles/wiki pages with contextual data |

| Complementing Collection | Active pursuit of additional objects to be included in a (Web)exhibit or collection |

| Classification | Gathering descriptive metadata related to object in a collection. Social tagging is a well-known example. |

| Co-curation | Using inspiration/expertise of non-professional curators to create (Web)exhibits |

| Crowdfunding | Collective cooperation of people who pool their money and other resources together to support efforts initiated by others. |

Another model of public participation is portrayed by Nina Simon (2010) in The Participatory Museum. She basically applies the three models of Public Participation in Scientific Research (PPSR) to cultural institutions, adding a fourth model (Hosted projects):

Table 2. Public participation models (based on Simon, 2010)

| Public Participation Model | Description |

| 1. Contributory projects | Visitors are solicited to provide limited and specified objects, actions, or ideas to an institutionally controlled process. Comment boards and story-sharing kiosks are both common platforms for contributory activities. |

| 2. Collaborative projects | Visitors are invited to serve as active partners in the creation of institutional projects that are originated and ultimately controlled by the institution. |

| 3. Co-creative projects | Community members work together with institutional staff members from the beginning to define the project’s goals and to generate the program or exhibit based on community interests. |

| 4. Hosted projects | The institution turns over a portion of its facilities and/or resources to present programs developed and implemented by public groups or casual visitors. This happens in both scientific and cultural institutions. Institutions share space and/or tools with community groups with a wide range of interests, from amateur astronomers to knitters. |

Simon’s framework is mainly focused on the management of the relation between institutions and visitors/public. Those models of participation do not refer explicitly to crowdsourcing (as a type of participative online activity in which the public voluntarily undertake a task); however, the notions of “public participation” and “crowdsourcing” in the cultural domain can in some cases overlap.

In our study, we took a different perspective to classify crowdsourcing, and we focused on the tasks that participants are asked to perform.

As the analysis of the thirty-six initiatives progressed, two main trends emerged:

- Crowdsourcing projects that require the “crowd” to integrate/enrich/reconfigure existing institutional resources

- Crowdsourcing projects that ask the “crowd” to create/contribute novel resources

For instance, the Victoria and Albert Museum (London) has a collection of 140,000 images selected from a database automatically and, as a result, some of them may not be the best view of the object to display on the homepage of Search the Collections. Through a bespoke application, the public is invited to select the best images to be used. In contrast, the StoryCorps initiative (United States) aims at recording, sharing, and preserving Americans’ personal histories. Since 2003, StoryCorps has collected and archived more than 40,000 interviews with nearly 80,000 participants, thus creating an original and endless archive.

In the first group, the projects require the public to “interact” with digital and/or physical artefacts provided by the institution (e.g., storytelling on museums’ objects; tagging on galleries’ digital collection); hence, the public contribution appears to be interdependent with institutional collections. The public is asked to “intervene” on existing resources. The digital/physical artefacts made available drive participants’ tasks (e.g., tagging a painting; transcribing hand-written notes).

In the second group, projects ask the public to provide digital and/or physical contributions (e.g., information, personal memorabilia, videos, photos) to build a novel resource. The public contributions are not interdependent with existing collections, even though they may improve an institutional collection with additional resources. Commonly, the type (e.g., audio, photos) and the theme (e.g., private conversations) of contributions are determined by the project, whereas the contributors determine the content of their contributions (e.g., the subject of the private conversation).

A further analysis of the two groups of crowdsourcing projects led to the identification of the most common tasks per group.

- When interacting with an existing collection, the public is mostly asked to intervene in terms of curation (e.g., social tagging, image selection, exhibition curation, classification); revision (e.g., transcription, correction); and location (e.g., artworks mapping, map matching, location storytelling).

- When developing a new resource, the public is mostly invited to share physical or digital objects, such as document private life (e.g., audio/video of intimate conversations); document historical events (e.g., family memorabilia); and enrich known locations (e.g., location-related storytelling).

Integration and reconfiguration of existing assets

Within the projects that complement existing collections, the types of contribution have been classified in terms of Curating, Revising, and Locating.

Curating

Curating implies selecting, classifying, describing, and organising given objects. As mentioned before, the Victoria and Albert Museum invites the public to select the best images to be used in the Search the Collections tool.

The Brooklyn Museum (U.S.) and Kröller-Müller Museum (Netherlands) have organised public-curated exhibitions. Click! A Crowd-Curated Exhibition (Brooklyn Museum) first collected works of photography through an open call and then asked the audience to evaluate the works. Finally, the works were exhibited depending on their relative ranking resulted from the public evaluation.

In 2010, the Kröller-Müller Museum organised two public-curated exhibitions based on a selection of artworks of its own collection: Expose: My Favourite Landscape was entirely curated by children who, through a website, chose their favourite landscapes among a set of fifty proposed by the Museum and gave their reasons why the works had to be included in the exhibition. Twenty artworks were then exhibited.

Among the thirty-six initiatives analysed, tagging is a frequent crowdsourced classification task. Steve Museum (U.S.) is probably the one of the oldest and most known projects (since 2005). Tag! You’re it! is Brooklyn Museum’s initiative organised as a game.

Tagging is not simply limited to textual labels attached to artworks. First Impressions is an experimental project by the Indianapolis Museum of Art (U.S.) that asks participants to click on the first thing that catches the attention as they look at a series of artworks. All clicks are collected to create heat maps.

Revising

Revising implies analysing, reconsidering, correcting, and improving given objects. For instance, Freeze Tag by the Brooklyn Museum was launched as a follow-up to Tag! You’re it! to review the tags provided by the public. Participants are presented with tags that have been flagged for removal by other members. The task is to provide a second opinion about the relevance of the tag.

The Ancient Lives project, promoted by the Citizen Science Alliance (CSA), asks the general public to transcribe Greek papyri fragments through a bespoke application.

Another CSA initiative, Old Weather, invites participants to transcribe weather-handwritten observations made by Royal Navy ships around the time of World War I. These transcriptions will help historians track past ship movements and the stories of the people on board, as well as develop climate model projections.

For the past years, libraries have been highly committed to digitisation. Optical character recognition (OCR) delivers different results depending on the condition of the original material and on “readability” of fonts. For historical documents, the results of electronically translated text can be often poor. The National Library of Australia and National Library of Finland have involved the public in the correction of digitised text of historic newspapers.

Locating

Locating implies placing given objects in physical space, telling stories, and providing information on locations. Initiatives in map-based websites (e.g., Historypin) are increasing, but they have been largely managed by the cultural institutions, without the active contribution of the public. Crowdsourced mapping seems a more recent emergence in the cultural domain. The Map the Museum project (2012) by the Royal Pavilion & Museums of Brighton and Hove (United Kingdom) invites the public to place the objects of the collection on a map, and possibly to provide additional information on them.

1001 Stories of Denmark displays stories about places written by 180 countries’ experts on cultural heritage and history. The website is user driven: participants can contribute with comments, photos, stories, and recommendations, and can place new dots on the map and create new routes. Beyond the map visualisation, locations are also displayed in a timeline.

Creation of new assets

Within the projects, which build new collections, types of contribution can be classified in terms of documenting personal life, documenting history, and augmenting locations.

Documenting personal life

Documenting personal life refers to crowd contributions related to intimate moments and events. For instance, YouTube asked the public to film their personal life on a single day, July 24, 2010. Life in a Day became a film 94 minutes and 57 seconds long, including scenes selected from 4,500 hours of footage in 80,000 submissions from 192 nations.

Meanwhile, the Listening project invites the public to record intimate conversations. Some of these conversations are broadcast by the BBC and curated and archived by the British Library.

This initiative was inspired by the aforementioned StoryCorps project. Within StoryCorps, each conversation is recorded on a free CD to share, and is preserved at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. StoryCorps is one of the largest oral history projects of its kind, and millions listen to the weekly broadcasts on NPR’s Morning Edition and on the project listen page.

Documenting history

Documenting history refers to crowd contributions related to historical events. For instance, StoryCorps, in partnership with the 9/11 Memorial Museum, aims to record at least one remembrance for each of the victims of the terrorist attacks on February 26, 1993, and September 11, 2001; as well as the narratives from survivors, rescue workers, witnesses, service providers, and other such persons impacted by these events in order to preserve their personal experiences. A public StoryCorps StoryBooth has been located in Manhattan (Foley Square) to collect interviews.

The 9/11 Memorial is also actively acquiring materials for its permanent collection (e.g., photos, videos, voice messages, personal effects, workplace memorabilia, incident-specific documents). Make History is the collective endeavour to tell the events of 9/11 through the eyes of those who experienced it, both at the attack sites and around the world.

Similarly, the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre in Rwanda created an oral testimony project with the goal of recording and preserving the experiences of the 1994 Rwanda genocide survivors.

Wir waren so frei, promoted by the Deutsche Kinemathek and the Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (Germany), is building a collection on the fall of the Berlin Wall and German reunification. The Internet archive has its origins in the 2009 exhibition “Moments in Time 1989/1990” at the Museum for Film and Television in Berlin. A selection curated from the submitted photographs and films formed the centre of the exhibition. This was juxtaposed with images from international television broadcasts and German documentary films.

Augmenting locations

Augmenting locations refers to crowd contributions related to places. For instance, the Sound Map project by the British Library asked the public to record sounds of their environment at home, at work, etc.

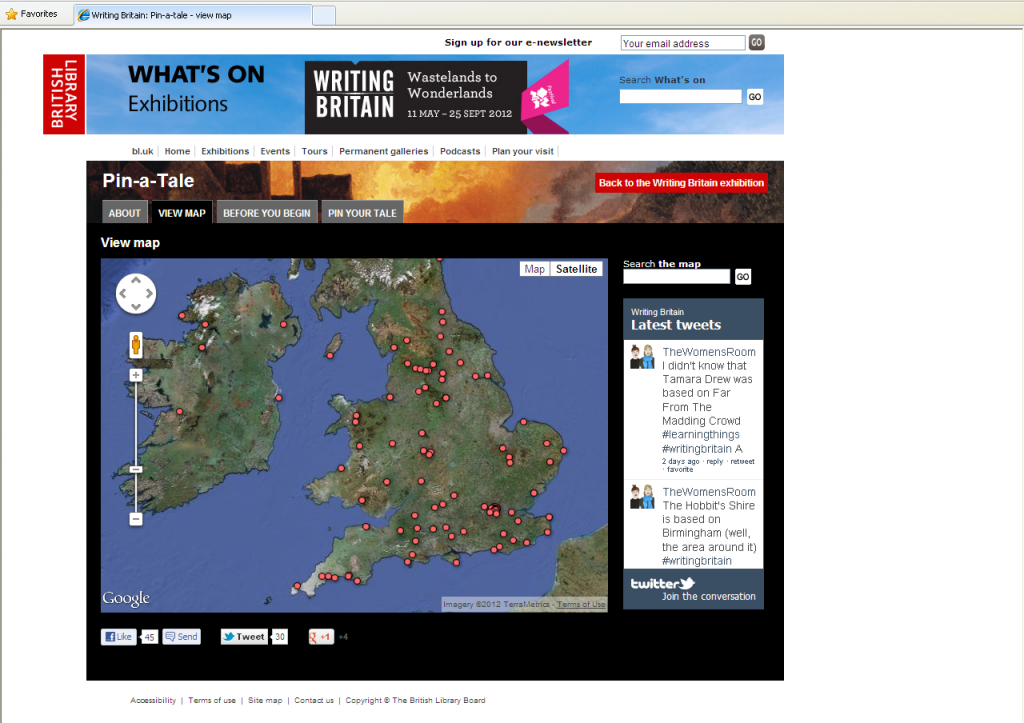

Pin-a-Tale, promoted by the British Library, was linked to the “Writing Britain – Wastelands to Wonderlands” exhibition (May/September 2012) and explored how landscapes and places of Britain permeate literary works. The public was asked “to curate a comprehensive literary landscape of the British and Irish Isles”: they could choose a piece of writing representing a known place, reference the location, and then drag the pin to refine the location.

The crowd

In our adopted definition of crowdsourcing, the crowd is “a group of individuals of varying knowledge, heterogeneity, and number,” who voluntarily undertake a task proposed by an organisation (Estelles-Arolas & Gonzalez-Ladron-de-Guevara, 2012). Fifty percent of the definitions of crowdsourcing studied by Estelles and Gonzalez describe the crowd as a large group of individuals. In their study, they refer to other authors who define the type of crowd as “users or consumers, considered the essence of crowdsourcing; […] as amateurs (students, young graduates, scientists or simply individuals), although they do not set aside professionals; […] as web workers.”

Whilst the typology of public did not surface (e.g., amateurs, professionals, etc.) from the websites surveyed, it is possible to examine the number of people and the relation between the institution and the “crowd.” Among the thirty-six initiatives analysed, fifteen declare the number of contributors in their websites. Numbers vary greatly. The “crowd” in the fifteen initiatives oscillates from a few hundred to thousands to tens of thousands; however, most of them involve around or less than 5,000 to 6,000 participants.

There are many variables that may affect the number of participants (e.g., type of task, project duration, dissemination), but they were not part of the study. It is nonetheless relevant here to underline that the idea of the crowd as a “large group of individuals” is not supported by the findings. The participants in the digital humanities crowdsourcing projects are still a limited number. A few hundred or thousands of participants in a crowdsourcing initiative may be a significant number; nonetheless, it seems narrow when we consider the millions of people surfing the Web on a daily basis, actively interacting online (e.g., commenting and uploading multimedia files on YouTube, Flickr, Facebook), or participating in other crowdsourcing initiatives (e.g., Wikipedia, Galaxy Zoo).

Another aspect observed in the projects surveyed is the relationship to the contributors. Our adopted definition describes crowdsourcing as “a type of participative online activity,” so we may argue that interactions with the participants occur exclusively online. Nonetheless crowdsourcing projects in many fields, as well as for most of the initiatives examined in the digital humanities, adopt a blended approach, combining crowdsourcing “face-to-face” events with “standard” computer-mediated actions. For instance, the Welsh Voices of the Great War Online project, by the Cardiff School of History, Archaeology and Religion, crowdsourced materials (e.g., letters, photos, physical memorabilia) mainly through roadshows, and partially online. The resources gathered were then catalogued, digitised, and shared online.

“Adding your story to Europeana 1914-1918,” promoted by the Europeana 1914-1918 project, is based on an initiative at the University of Oxford, The Great War Archive, where people across Britain were asked to bring personal memorabilia from the War to be digitised. Europeana 1914-1918 focuses on collecting memorabilia of the Great War from several European Countries. Contributions to Europeana 1914-1918 can be made online through the project website, or face to face during the collection days, when items brought by people are photographed by the project staff. The public is also encouraged to organise their own collections day events to digitise and add material for Europeana 1914-1918.

The WALL, by the Museum of Copenhagen, is an approximately 12-meter-long outdoor multitouch screen that can be experienced at different sites throughout the city, showing a mixture of material from the museum’s collections, as well as from public contributions. People can contribute through the dedicated website, and at the WALL.

The findings show that crowdsourcing in the digital humanities is not limited to interactions with the digital audience, but can take a hybrid approach where physical and online interactions are intertwined. It seems also predictable that this approach will affect mostly crowdsourcing initiatives aiming at documenting historical events, where personal memorabilia provided by the public play an important role.

In the initiatives surveyed, the “crowd” is not only asked to perform tasks computationally difficult or impossible, but also invited to share tangible and intangible resources that are “owned” by them to enrich existing collections, or to develop new ones. In the latter case, the crowdsourcing process is undertaken to seek information, stories, and items provided by specific groups of people, motivated by a sort of “relation” with the resource provided (e.g., personal stories, family memorabilia, familiar locations, known literature).

4. Design recommendations

The findings suggest that there is no “one-solution-fits-all” design for crowdsourcing in digital humanities. Furthermore, crowdsourcing is a recent phenomenon that posits sociotechnological challenges, as well as concerns about the convergence of professional and general public knowledge. Nevertheless, a few reflections can be made to support the development of crowdsourcing initiatives.

Purpose

The main aims of the thirty-six projects surveyed can be summarized as the following:

- Exploring new forms of public engagement (Tag! You’re it!; Expose: My Favourite Landscape)

- Enriching institutional resources through the contribution of the crowd (Transcribe Bentham; Old Weather)

- Building novel resources (e.g., archive) through the contribution of the crowd (The Ghostsigns project; 9/11 Memorial Museum)

It may seem obvious to firstly focus on the purpose; however, it is important to understand that, depending on the purpose, the impact of the crowd contribution changes. In the first case (public engagement), the organisation is basically expanding one of its institutional roles in alternative ways and through new tools. The public is invited to interact with institutional resources in new ways, enriching them, even if not directly impacting them.

Conversely, when an institution involves the public to enrich or build cultural resources, complex issues arise: How can we integrate the contribution of the crowd with institutional collections? How can we facilitate convergence of professional and amateur knowledge? How do we assure the quality of the crowd-contributed content? How can we design a system that supports the combination of crowd-contributed content and institutional content? These questions are often hard to answer (even though some “older” experiences, such as Wikipedia or the Galaxy Zoo project, may help); nonetheless, they should be considered when planning a crowdsourcing initiative.

Scale

This study found that the crowdsourcing initiatives can be temporary (e.g., lasting a few months) or open (e.g., no scheduled ending). They can be temporary because they are linked to a specific event or exhibition, due to budget limitations, or because of a specific choice of the institution to run the crowdsourcing “experiment” for a limited time. They can also have no scheduled ending, like StoryCorps, which permanently collects people’s interviews, or like the Australian Newspaper Digitisation Program, which will predictably end when all the tasks are accomplished (OCR correction).

Based on the projects analysed, it is suggested that institutions with a large amount of digital resources to be improved through crowdsourcing should segment their initiatives into smaller (e.g., thematic) sub-projects, which can be completed in a shorter time. In fact, from the study, we believe that temporary and small-scale initiatives tend to achieve their objective; however, further research is needed to support this hypothesis.

Audience

The crowd is “a group of individuals of varying knowledge, heterogeneity, and number” (Estelles-Arolas & Gonzalez-Ladron-de-Guevara, 2012). If this definition can be applied equally to commercial and non-commercial crowdsourcing projects, a further specification is required. In the profit sector, crowdsourcing is a paid activity that involves a variety of contributors, mainly for economic reasons. In the non-profit sector, the perspective is quite different. Previous research shows that there is a correlation between active engagement and personal interests in cultural crowdsourcing initiatives (Carletti, 2011a). Furthermore, in the cultural sector, volunteering has a long and consolidated tradition, and unpaid work is done for a common good. Even if crowdsourcing projects rely on free contributions, the notion of crowdsourcing is more extensive than that of digital volunteering. Volunteering refers to people who freely offer to undertake a task or work for an organization without being paid. In the digital humanities, crowdsourcing refers to the process of aggregating distributed resources (e.g., information, artefacts) to improve existing assets or to create new ones.

Crowdsourcing projects in the digital humanities can be seen as novel paths of collaboration between institutions and their audiences. In fact, institutions are not merely “taking a function once performed by employees and outsourcing it to an undefined (and generally large) network of people” (Howe, 2006); they are collaborating with their public to augment or build digital assets through the aggregation of dispersed resources.

The crowd in the majority of crowdsourcing initiatives is “undefined,” whereas in the digital humanities, the crowd seems to be primarily the public of the institution. Hence, institutions already have a relation with their actual or potential contributors. This existing relation between institution and public represents a relevant starting point and should be enhanced when launching a crowdsourcing process.

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to offer a picture of the emerging crowdsourcing practices in the digital humanities. Our analysis of thirty-six crowdsourcing projects led to the identification of two main tendencies (improving existing collections; developing novel resources) and to the classification of the most frequently crowdsourced tasks. The findings contributed also to shed the light on the dimension of the crowd and on the relation between institution and their audience.

Finally, the paper stimulated some reflections on the purpose, scale, and audience of crowdsourcing projects in the digital humanities. Crowdsourcing in this field seems to have quite distinctive features and a main challenge. The notion of crowdsourcing refers to the efficient outsourcing of an activity to an external contributor. The task performed by the external contributor is an integral part of the process; however, among several of the projects surveyed, a separation occurs between the organisations’ workflows and the crowdsourced activities, between the institutional resources and the crowd contributions. The resources contributed by the crowd are not incorporated into the institutional collections. As a result, the open challenge for crowdsourcing in the digital humanities is how to integrate institutional and crowd-contributed content. This study suggests the value of investigating sociotechnological systems that can support the collaboration between cultural institutions and their public, as well as to combine efficiently multisource content.

Further, our research advocates that there is vast expertise, dedication, and willingness to provide digital resources on specific topics, and the work of the amateur is creating new information that others can use and refer to, often in areas that are not covered by traditional institutions (Finnegan, 2005; Terras, 2010). Crowdsourcing seems to require a mutual exchange between institution and public, as well as an alternative conceptualisation of knowledge as a “history of interaction between outsiders and establishments, between amateur and professionals, intellectual entrepreneurs and intellectual rentiers” (Burke, 2000: 51). Rethinking the relationship between official and unofficial knowledge is probably the main challenge that cultural institutions have to face when undertaking a crowdsourcing process.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Council UK’s Horizon Digital Economy Research Hub grant, EP/G065802/1.

References and Bibliography

Benkler, Y., & H. Nissenbaum. (2006). “Commons-based peer production virtue.” The Journal of Political Philosophy 14 (4), 394–419.

Bryant, S. L., A. Forte, & A. Bruckman. (2005). “Becoming Wikipedian: Transformation of participation in a collaborative online encyclopedia.” Human Factors, 1–10.

Bültmann, B., R. Hardy, A. Muir., & C. Wictor. (2005). Digitised content in the UK Research Library and Archives Sector. JISC/CURL.

Burke, P. (2000). A social history of knowledge. From Gutenberg to Diderot. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Carletti, L. (2011a). A grassroots initiative for digital preservation of ephemeral artefacts: the Ghostsigns project. Digital Engagement Conference 2011. Consulted. http://de2011.computing.dundee.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/A-grassroots-initiative-for-digital-preservation-of-ephemeral-artefacts-the-Ghostsigns-project.pdf

Carletti, L. (2011b). Enhancement of niche cultural and social resources through crowd-contribution: the creation of the Ghostsigns online archive. Digital Resources in Humanities and Art Conference 2011. Consulted. http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/drha/programme/speakers.aspx

Chrisbatt Consulting. (2009). Digitisation, curation and two-way engagement. JISC Report.

Clarke, P., & J. Warren. (2009). “Ephemera: Between archival objects and events.” Journal of the Society of Archivists 30(1), 45–66.

Coleman, D. J., Y. Georgiadou, & J. Labonte. (2009). “Volunteered geographic information: The nature and motivation of produsers.” International Journal of Spatial Data Infrastructures Research 4, 332–358.

Damodaran, L., & W. Olphert. (2006). Informing digital futures – Strategies for citizen engagement. Dordrecht: Springer.

Dron, J. (2007). “Designing the undesignable: Social software and control.” Educational Technology & Society 10(3), 60–71.

Estelles-Arolas, E., & F. Gonzalez-Ladron-de-Guevara. (2012). “Towards an integrated crowdsourcing definition.” Journal of Information Science, accepted for publication.

Finnegan, R. (2005). “Introduction: Looking beyond the walls.” In R. Finnegan, Participating in the Knowledge Society: Research beyond University Walls, 1–20. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Holley, R. (2010). Crowdsourcing: How and why should libraries do it? D-Lib Magazine 16(3/4).

Howe, J. (2006). “The rise of crowdsourcing.” Wired.com. Consulted. http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/14.06/crowds.html

Keen, A. (2007). The cult of the amateur. New York: Doubleday .

Kittur, A., E. H. Chi, & B. Suh. (2008). “Crowdsourcing user studies with mechanical turk.”

Proceedings of CHI 2008, 453–456. Firenze, Italy.

Latham, R., & S. Sassen. (2005). Digital formations – IT and new architectures in the global realm. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lee, A., C. Danis, T. Miller, & Y. Jung. (2001). “Fostering social interaction in online spaces. Proceedings of Human-Computer Interaction 2001. New Orleans, Louisiana (USA).

Nov, O., D. Anderson, & O. Arazy. (2010). “Volunteer computing: A model of the factors determining contribution to community-based scientific research.” Proceedings of the International world Wide Web Conference Committee. 26–30 April, Raleigh, North Carolina (USA).

Nov, O., O. Arazy, & D. Anderson. (2011). “Dusting for science: Motivation and participation of Digital Citizen science volunteers.” Proceedings of iConference 2011, 68–74. Seattle, Washington (USA).

Nov, O., M. Naaman, & C. Ye. (2009). “Motivational, structural and tenure factors that impact online community photo sharing.” Proceedings of the Third International ICWSM Conference. 17-20 May. San Jose, California (USA).

Oomen, J., & L. Aroyo. (2011). “Crowdsourcing in the cultural heritage domain: Opportunities and challenges.” Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Communities and Technologies. 19 June–2 July. Brisbane, Australia.

Oomen, J., L. B. Baltussen, S. Limonard, M. Brinkerink, A. van Ees, L. Aroyo, et al. (2010). “Emerging practices in the cultural heritage domain – Social tagging of audiovisual heritage.” Proceedings of the WebSci10: Extending the Frontiers of Society On-Line. April 26–27. Raleigh, North Carolina (USA).

Poole, N. (2010). The cost of digitising Europe’s cultural heritage. Comité des Sages of the European Commission.

Roberts, S., & L. Carletti. (2012). Digital Engagement & the History of Advertising Trust Ghostsigns Archive. History Workshop Online .

Shirky, C. (2010). Cognitive surplus – Creativity and generosity in a connected age. New York: Penguin Press.

Simon, N. (2010). The participatory museum. Consulted. http://www.participatorymuseum.org/read/

Terras, M. (2010). “Digital curiosities: resource creation via amateur digitization.” Literary and Lingusitic Computing 25(4), 425–438.

Warwick, C., M. Terras, P. Huntington, & N. Pappa. (2006). The LAIRAH Project:Log Analysis of Digital Resources in the Arts and Humanities. Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Warwick, C., M. Terras, P. Huntington, & N. Pappa. (2008). “If you build it will they come? The LAIRAH study: Quantifying the use of online resources in the arts and humanities through statistical analysis of user log data.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 23(1), 85–102.

Cite as:

L. Carletti, D. McAuley, D. Price, G. Giannachi and S. Benford, Digital Humanities and Crowdsourcing: An Exploration. In Museums and the Web 2013, N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). Silver Spring, MD: Museums and the Web. Published February 5, 2013. Consulted .

https://mw2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/digital-humanities-and-crowdsourcing-an-exploration-4/

2 thoughts on “Digital Humanities and Crowdsourcing: An Exploration”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I recently presented a session at the GEM conference in Leeds on crowdsourcing, and developed a blog (http://crowdsourcingthemuseum.tumblr.com/) to bring together case-studies and articles, as well as to promote discussion beyond the session. I have shared a link to this article in one of the posts and drew on the definitions, discussions and case-studies mentioned in this article throughout the presentation.

Hi Stuart, I’ve just had the chance to go through your presentation and it was very interesting, as my focus on crowdsourcing is related to my research on mechanisms of engagement. You might be also interested in a workshop that we are organising on Knowledge co-creation between organisations and the public. The deadline for the Call for Participation is on December 1st. Info on the website.