Transforming the Art Museum Experience: Gallery One

Jane Alexander, USA, Jake Barton, USA, Caroline Goeser, USA

Abstract

How can art museums use interpretive technology to engage visitors actively in new kinds of experiences with works of art? What are the best strategies for integrating technology into the project of visitor engagement? The Cleveland Museum of Art has responded with the ground-breaking Gallery One, an interactive art gallery that opened to stakeholders on December 12, 2012, and went through a six-week testing period until its public opening on January 21, 2013. Gallery One draws from extensive audience research and grows out of a major building and renovation project, in which CMA has reinstalled and reinterpreted the entire permanent collection in new and renovated gallery spaces. The end result is a highly innovative and robust blend of art, technology, design, and a unique user experience which emerged through the unprecedented collaboration of staff across the museum and with award-winning outside consultants.

Keywords: multimedia installation, mobile application; interpretive interactive installation, augmented reality, interior wayfinding, image recognition, art museum, intergenerational learning

1. Introduction – Gallery One

Located at the entrance to the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), Gallery One welcomes visitors into an active, 13,000-square-foot space where art and technology provide a dynamic environment for visitor exploration. With entrances at both the main lobby and the museum’s new, centrally located atrium space, Gallery One can be accessed easily at different points during a museum visit. As part of an overall program of art interpretation and visitor outreach, Gallery One’s innovative blend of art and technology invites visitors to connect actively with the art on view through exploration and creativity. Designed for visitors of all ages, both novice and seasoned, the technology interfaces inspire visitors to see art with greater depth and understanding, sparking experiences across the spectrum from close looking to active making and sharing.

Figure 1: The Beacon, as seen through the entrance to Gallery One (photo courtesy of Local Projects)

In the main section of Gallery One, top quality works of art—including many visitor favorites—are organized into thematic groupings that cross culture, chronology, and media. Multi-touch screens embedded in the gallery space invite close examination of the objects on view. Placed 14 feet in front of the groupings of art objects, the screens offer interpretation and digital investigation of the art. In these interactives, each artwork in the installation is interpreted through storytelling hotspots with opportunities to explore artworks visually through magnification and rotation, and to discover their original context and location. Each interface has a series of “games” that invite visitors to engage with the art on view through questions and experiences.

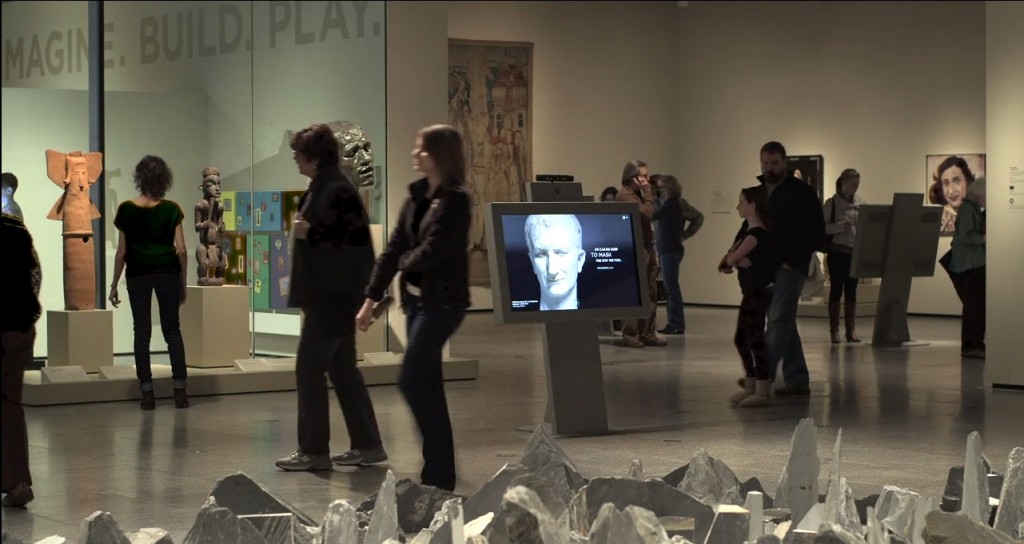

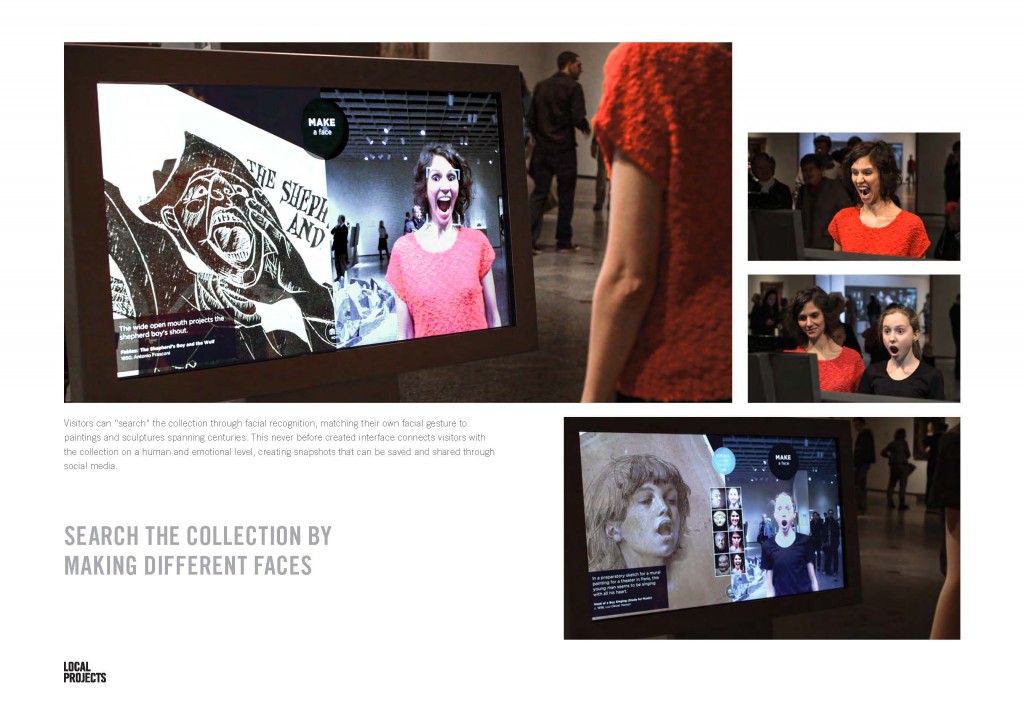

For example, one of the first art installations that visitors encounter is titled “How Do Our Bodies Inspire Art?” It offers a broad look at CMA’s encyclopedic collections of sculpture, including an ancient Roman marble athlete, a ceramic Japanese Haniwa figure, a wooden African sculpture, and a bronze head by Rodin. The games in the interactive that interprets this installation encourage visitors to connect actively with the collection and see themselves in the art on view. “Strike a Pose” invites visitors to explore figurative sculpture by asking them to match the pose of a sculpture they see on the screen. A motion sensor records their pose, and the interactive determines how closely the visitor has approached the artist’s sculpted body. “Make a Face” offers visitors the chance to investigate the museum’s collection of portraits through face-recognition software. A webcam records their facial expressions and matches them to works in CMA’s collections. “Build in Clay” encourages visitors to make a sculpture in clay by virtually kneading, rolling, coiling, cutting, and assembling. Visitors can share all of their creations through email, Facebook, and Twitter.

Figure 2: How Do our Bodies Inspire Art? – View of the Sculpture Lens. Photo courtesy of Local Projects

Studio Play is a dedicated space within Gallery One that allows families to explore the museum’s collections and create art together through hands-on activities and interactive technology stations. Kids can use easels to create a colorful drawing, and parents can place it in a frame for all to see their work on the walls of CMA. Families can create a dramatic production with shadow puppets, based on works from CMA’s collection. They can also discover an interactive, multi-touch screen that allows them to make simple lines or squiggles. The interactive then reveals works of art in our collection that incorporate the same lines and squiggles. It’s a fun way for families to become visually familiar with the art they will see in CMA’s permanent collection galleries.

Figure 3: Line and Shape Interactive – Kids search the collection by drawing in Studio Play. Photo courtesy of Local Projects

At the section of Gallery One closest to the museum’s new atrium, a 40-foot multi-touch MicroTile Collection Wall dramatically visualizes all the works currently on view in CMA’s permanent collection galleries, plus some that are in storage— over 3,800 works of art. A few seconds later, the wall changes views, allowing visitors to see a series of focused groupings of objects from CMA’s collection, organized around curated themes like “Love and Lust,” “Funerary Art,” and “Dance and Music.” They will also see objects grouped by medium or geographical region, drawn dynamically from CMA’s digital asset management system. This huge interactive tool allows visitors to see the permanent collection as a living organism, changing depending on the prism through which you view it. The Collection Wall further functions as a giant group and individual touchscreen interactive, and allows visitors to touch the objects represented on the wall to make discoveries. Visitors follow their curiosity through a visual interface that links each artwork to a series of associated artworks, giving visitors the opportunity to browse and explore relationships from object to object. Visitors can favorite works of art and discover tours that then launch them on a pathway through the museum’s galleries.

Visitors may also use ArtLens, CMA’s new iPad app, to deepen their experience. Visitors can download it for free to their iPads, or pre-loaded iPad 4’s are available to rent on location for a nominal fee of five dollars. The app is designed for three visitor behaviors:

- The “Near You Now” function allows visitors to browse and find digital interpretation of works of art they like based on proximity. Content is designed in short segments of audio and video, allowing visitors to choose what they want rather than committing to a long, linear narrative. Visitors can hear from curators, educators, and community members to discover the continuing traditions that bring art to life.

- The “Tours” function allows visitors to have a more structured experience in the galleries, taking a tour curated for the block of time they have available. They can walk through the galleries with CMA’s director to discover his favorites, or they can follow a theme that carves a focused path through the museum’s galleries. The two hundred most recently saved Visitor-created tours are also available.

- The “Scan” function uses image recognition to allow visitors to scan two-dimensional art objects to trigger texts or videos to pop up on the iPad screen. The immediate delivery of this additional interpretive content enables visitors to delve more deeply into the app to learn more about a work of art.

Figure 4: Using ArtLens, visitors can take a tour of their own creation, by favoriting artworks in ArtLens and on the Collection Wall. Photo courtesy of Local Projects

In an unprecedented combination of technology interfaces, borrowed or visitor-owned iPads can be docked at the Collection Wall, where visitors can save objects from the wall to the ArtLens app, creating a playlist of favorites. Visitors can author a custom tour from their list of favorites, saving their tour in ArtLens and on the Collection Wall for other visitors to discover. Through this feature, ArtLens provides an iPad experience that allows visitors to navigate throughout the museum, both physically and virtually from off site, providing far-reaching access to media-rich stories for CMA’s treasured works of art. Taken together, this suite of new interfaces transforms the visitor experience by extending the access and creative agency of each individual visitor.

Development through Innovative Collaboration

The development of Gallery One and Art Lens represents a true and equal collaboration among the curatorial, information management and technology services, education and interpretation, and design departments at the Cleveland Museum of Art. The development process was guided by CMA’s chief curator and deputy director, an atypical and noteworthy approach among museums in the design of interactive technology spaces. This collaborative organizational structure is groundbreaking, not just within the museum community, but within user-interface design in general. It elevated each department’s contribution, resulting in an unparalleled interactive experience, with technology and software that has never been used before in any venue, content interpreted in fun and approachable ways, and unprecedented design of an interactive gallery space that integrates technology into an art gallery setting. The museum also partnered with award-winning outside consultants to realize the project, including Local Projects (media design and development), Gallagher and Associates (exhibit design), Zenith Systems (AV Integration), Piction Digital Image Systems (CMS/DAM development), Earprint Productions (app content development), and Navizon (wayfinding).

2. Goals of Gallery One: Empowering visitors

While the idea of an interactive space was part of the museum’s original plan in the building and renovation project that broke ground in 2005, the new Gallery One collaborative team was put in place in 2010. At that time, the following goals were established for an interactive gallery that would:

- Create a nexus of interpretation, learning, and audience development

- Build audiences—including families, youth, school groups, and occasional visitors—by providing a fun and engaging environment for visitors with all levels of knowledge about art

- Highlight featured artworks in a visitor-centered and -layered interpretive manner, thereby bringing those artworks to the Greater Cleveland community and the world

- Propel visitors into the primary galleries with greater enthusiasm, understanding, and excitement about the collection

- Develop and galvanize visitor interest, bringing visitors back to the museum again and again

Development efforts centered on providing visitors to this new space with a transformative experience, allowing them to:

- Feel empowered to browse, explore, and create personal meanings about the museum’s collection

- Enjoy an organic, visitor-driven experience in the space without feeling like the experience is haphazard

- Employ engaging interactives, both technological and hands on, that use investigative methods and tools for critical observation to develop an engagement with the collection and interpretive concepts about the collection

- Create a personalized profile driven by their interests

3. Audience research: Putting the visitor front and center

In 2009, CMA began a concerted effort to make visitors central to the reinstallation and reinterpretation of the permanent collection by evaluating visitor responses to the earliest phase of gallery reinstallations. As a critical component of this initiative, Gallery One is a fundamental expression of the museum’s broader efforts to refine its relationship with audiences in Greater Cleveland and beyond.

In gathering data from its visitors, CMA has taken advantage of transformations in the fields of museum education and visitor studies that have provided new ways of understanding museum visitor behavior. Rather than collecting data on demographic information alone, experts have found that collecting information on how visitors tend to behave in museums and what motivates their visits can provide a more nuanced visitor profile to guide museum interpretation and program development. In 2009, John Falk released Identity and the Museum Visitor Experience, an important study that shifted thinking from characterizing visitors by demographics alone to segmenting their motivational behavior by individual experience-seeking styles. The Dallas Museum of Art followed in 2011, with Ignite the Power of Art (Pitman & Hairy, 2011) detailing their long-term research initiative to understand the triggers that engage visitors with art. Both of these models capture the spirit of the work begun at CMA: to learn our visitor styles and what ignites their visiting museum experiences. These efforts can be seen as an extension of the museum’s long-standing focus on art and education, which were given expression in the groundbreaking 1994 publication The Visitor’s Voice, which summarized the findings of a three-year program of audience research and evaluation that informed the installation of CMA’s galleries of Renaissance and Baroque art (Schloder, Williams, & Mann, 1993).

At the CMA in 2009, a major visitor study conducted by Marianna Adams of Audience Focus, Inc. allowed us to ascertain how visitors were making meaning in the newly reinstalled galleries of European and American art, circa 1600 to 1800. In this summative evaluation of the interpretive strategies employed by the museum in the historic 1916 Building, Adams asked: how were the interpretive themes that we had chosen for the new galleries received by our visitors? How could the lessons we learned as a result of the study be applied in future installations?

The study conveyed that many of the visitors to our permanent collection galleries can best be characterized as browsers, not seeming to have a predefined agenda for their visit other than gravitating to the works of art to which they respond strongly based on their tastes and prior knowledge. In the aggregate, visitors told us that they had not really thought about overarching themes that organized the works in a gallery, but were more drawn to individual works of art. Accordingly, they tended not to read the interpretive introductory gallery texts, but instead read object labels if they wanted to know more about a work they liked.

Figure 5: CMA galleries make visitors central to the reinterpretation of the permanent collection. Photo courtesy of Local Projects.

This browsing mode, from object to object, provides a challenge to museum educators and curators who have conceived of the permanent collection gallery as a unit, with broad concepts organizing the individual works into a cohesive whole. If visitors were not picking up on the thematic concepts, how could the interpretation have been successful? Jay Rounds, professor of museum studies at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, addressed this conundrum in Curator (Rounds, 2006):

Visitors come to museums for their own reasons, and those reasons are not necessarily congruent with the goals of the museum. No doubt their browsing through exhibits is suboptimal when compared against [a] museum’s goal that visitors “engage in systematic study or exploration.” But the same [browsing] behavior may prove to be an intelligent response to the situation when measured against the goals of the visitors themselves.

Rounds opened our eyes to the implications of our own visitor study. Art museum visitors don’t behave as students—why should they? They have a variety of reasons for their visits, many related to leisure-time pursuits. We have them for an average of six minutes per gallery—which is actually longer than visitors at other museums. As a result of our research, we now ask ourselves, how can we hook visitors as they browse, and how can we provide the kind of interpretation that will open up our expectations and honor visitors’ browsing behavior?

Responding to audience research: the conception behind Gallery One and ArtLens

Gallery One is conceived and approached as an interactive space that seeks to connect art and ideas, forge connections between art and people, and provide visitors with tools that enhance their permanent-collection gallery experiences. The Gallery One space brings art and ideas together to facilitate inquiry and discourse among visitors. Information is delivered in ways that feel like experiences rather than didactic lessons, allowing visitors to drive their own encounters with works of art and share their experiences with each other. In doing so, the museum looks to visitors to engage each other in the collections rather than positioning the museum as the sole voice and arbiter of the visitor experience. Gallery One is aimed at both novice and experienced visitors, and encourages people to use the museum as a place to spend time learning, exploring, and having fun with each other.

Gallery One is organized in three sections, each asking visitors a question to engage them in their experience: (1) What is it, and what do you see? (2) How is it made? (3) Why was it made? This approach privileges inquiry-based techniques for exploring the collections, and seeks to open new perspectives on the visual arts by moving away from the conventional, art-historical narratives as the central, overarching portal into the collection. Large interactive stations take the form of horizontal lenses aimed at groupings of art and focused on a specific question. This format encourages visitors to use the interactive lens as a kind of transparent tool—to see through the technology for better understanding and enjoyment of the art objects. The interactive lenses are carefully engineered to allow visitors to enhance their experience of viewing without creating a barrier to the physical works of art.

The Collection Wall is conceived as a tool for visitors to browse CMA’s encyclopedic collection, and serves as a fulcrum between Gallery One and the permanent collection galleries. It is designed to propel visitors into the galleries by giving them a taste of the objects in the collection and allowing them to create their own customized visit by downloading objects and tours to their iPad. In this way, Gallery One is conceived as an interactive space that is deeply connected to the entire museum and to the overall gallery interpretation program, which has been recognized as a model for art museums with a generous and prestigious NEH Challenge Grant awarded in 2012.

The ArtLens app is conceived as a tool designed for multiple visitor behaviors, responding directly to the lessons learned in our own and in new visitor studies. Most importantly, it honors the browsing mode we know so many of our visitors adopt in the galleries, allowing visitors to scan works to find digital interpretation for works they gravitate toward as they browse through the galleries. Further, in creating audio and video interpretation with multiple voices and perspectives and experts and community members in conversation, ArtLens is designed to model and spark conversation among our visitors as they respond to works of art in the galleries. ArtLens also enables visitors to share their favorite objects in CMA’s collections through social media, to further extend conversations and interpretation. As the New Media Consortium’s 2010 Horizon Report: Museum Edition suggests, “Increasingly, museum visitors (and staff) expect to be able to work, learn, study, and connect with their social networks in all places and at all times using whichever device they choose”; and “The abundance of resources and relationships offered by … social networks is challenging museum professionals to revisit their roles as educators” (Johnson et al., 2010). We are in the process of exploring how to monitor and further contribute to conversations about CMA’s objects that extend our iPad app interpretation into social media venues. We are networking with colleagues about successful forms of social media integration, social engagement, and interactivity, and are in active conversation with staff involved in the O-app at the Museum of Old and New Art, the Pinterest project at the Chicago History Museum, and the Art Clix app at the High Museum of Art (see Girardeau, 2012).

4. Specifications of the interactives: Hardware and software details

The Collection Wall is a dramatic 40-foot interface displaying over 3,800 artworks from CMA’s collection at once, most of which can be viewed in the galleries. The Collection Wall also presents thirty-two curated themes, which can be changed by museum staff on an ongoing basis. These views are looped in a 40-second cycle. Standing 5 feet by 40 feet, the wall is composed of 150 Christie MicroTiles and displays more than 23 million pixels, which is the equivalent of more than twenty-three 720p HDTVs. Every 10 minutes, an application content management system updates the wall with high-resolution artwork images, metadata, and the frequency each artwork has been “favorited” on the wall and within in the ArtLens iPad app. Users can save favorites to their iPad from the wall by setting their device in one of eight docking stations, which identify an iPad by detecting an RFID chip on the back of its case. The Christie iKit multi-touch system allows multiple users to interact with the wall, simultaneously opening as many as twenty separate interfaces across the Collection Wall to explore the collection. Software was written using open Frameworks and runs on two Windows 7 workstations supported by four Linux servers processing the video across the wall, and an RFID server managing the iPad station connectivity.

The visitor’s favoriting and sharing activity creates metrics that enable museum staff to understand what artworks visitors are engaging with, creating a feedback loop with the museum. Visitors can also queue curated themes to display on the Collection Wall, playing them like a jukebox that changes every 40 seconds. These themes can be changed dynamically by the museum, creating another mode of expression for staff, and connecting with temporary exhibitions or creating new ideas for the permanent collection.

The Beacon is a 4-by-4-foot array of 55-inch Edgelit 1080p LED displays located at the lobby entrance to Gallery One. It plays a looping, non-interactive program displaying both dynamic and pre-rendered content. Content for “Dynamic” elements is pulled from the Sculpture Lens. Individual face pairs from visitors playing the “Make a Face” game on the “Sculpture” lens are assembled into photo strips, with each photo strip containing four face pairs. New visitor photo content is loaded in at the start of each loop, approximately every six minutes. Content for top favorites is pulled from the network API. New content is loaded in at the start of each stage. The number of favorites is aggregated continuously over time, and the Beacon checks for updates to the favorites database every cycle. The content for the Beacon is generated and displayed in C++ and openGL, using the Cinder library. The entire loop is approximately six minutes long and cycles continuously. The events within the sequence incorporate the following: “playback” stages display only pre-rendered video; “rendered” stages display a composite of pre-rendered and generatively drawn elements; “dynamic” stages display content being pulled and rendered in real time. The Beacon deploys a video and communication bus to maintain uniform color across the entire display. It is driven by a remotely located Windows 7 workstation and extends video over Shielded Cat6 cable with digital extenders.

Figure 9: The Beacon, encouraging visitors to engage within Gallery One. Photo courtesy of Local Projects

The Lenses

In all, there are six interactive lenses in Gallery One, each composed of a large-format interactive 46-inch touch screen that interprets clusters of related artworks. Each lens is a 1080p HD display with a 32-point, optically-driven multi-touch overlay. The modular design of the lens housing provides for easy maintenance and minimizes down time. To give the lenses a small footprint in the gallery, the Windows PCs running the software for each lens are located in a remote server room. Audio is supported from a hidden overhead speaker system that utilizes an extremely narrow audio beam to isolate the audio to a 2-meter area where the user would be standing. The sculpture lens uses a Microsoft Kinect to track user skeletons for the “Strike a Pose” game, and a webcam to track faces for the “Make a Face” interactive. The software was written with a mixture of ActionScript 3/Adobe AIR and C++/openFrameworks.

The “Lion” installation was the first grouping of artworks that we chose and interpreted, and represents a significant break-through in conceptual planning for the entire team. We knew we wanted to develop a thematic arrangement that focused on animals, ever popular with a wide cross-section of visitors. We further wanted the grouping to allow visitors to investigate modes of artistic representation, from realism to various forms of stylization in artworks across time and cultures. We chose the lion as a familiar animal that visitors could readily call to mind, recognize when realistically represented, and be surprised by when rendered in an expressionistic or abstracted way. We also have a strong selection of works that reference lions from a variety of perspectives, across the collection. Local Projects was charged to develop a technology interface to engage visitors with these objects and concepts, using an interrogative and conversational style rather than didactic. They developed an innovative approach, conceiving of the fixed technology kiosk as a transparent lens onto the installation of artworks. They animated the top level of the interface with a question: What does a lion look like? The CMA team loved the simplicity of that question, which was a call to discovery, recognition, and surprise, and became the visitor’s entry point into the interpretive technology.

The lens software consists of a unified framework upon which a variety of interactive multimedia, games, and vignettes were built. All six lenses share a similar home screen layout, framing the artworks in front of the lens. Touching any artwork on the screen opens the “Look Closer” interactive, which shows high-resolution imagery of the artwork, many of which were photographed from multiple angles and may be rotated 360 degrees and zoomed by touch. The artworks reveal assorted informational hotspots relating to specific details of the work, the artist, era, etc. through slideshows, text, and video. In addition to the “Look Closer” mode, the lenses each have a theme and one or more unique interactive games designed around that theme.

Sculpture Lens

Make a Face. In real time, facial recognition software matches a visitor’s facial expression to artworks within CMA’s collection. The visitor’s expression is captured and the system measures nodal points on the face, distance between eyes, shape of the cheekbones and other distinguishable features. These nodal points are then compared to the nodal points computed from a database of 189 artwork pictures in order to find a match. The matched faces are collected into photo-booth-style strips that are then displayed on the Beacon near the gallery’s entry. The visitor is also able to email their ‘photo strip’ to themselves and share with others.

Figure 11: Visitors captured at the “Make a Face” game in the sculpture lens. Photo courtesy of Local Projects

Strike a Pose. The visitor is shown an image of a sculpture in a unique pose and asked to imitate that physical position. A Kinect sensor measures how closely their pose matches the original and assigns a percentage to indicate how well the visitor embodied the sculpture’s pose. The better the match, the higher the percentage achieved. The skeleton matching software uses a library of human-generated skeleton data captured via the Kinect data to quantify the match between the poses of a museum visitor and each sculpture. Visitors can email their image capture, see other visitors’ images, and try another pose.

Figure 12: Visitors captured at the “gesture” game in the Sculpture Lens. Photo courtesy of Local Projects

Figure 13: Visitors playing Expression game in Gallery One’s sculpture lens. Photo by Local Projects

Build with Clay. Visitors can construct their own clay sculptures in the same form as the Japanese Haniwa sculpture on display nearby. The process of creation is presented through an interactive, multi-touch, stop-motion video.

Lions Lens

Cast a Vote. This activity explores the ideas of realism in representation and of art as a visual language. Polling questions present a progression of thought about what a lion looks like and what a lion means, and aggregates answers in a cumulative interactive infographic.

Epic Stories Lens

Find the Origin. Visitors are asked to match historical and contemporary popular culture examples to three narrative archetypes that are represented within the artworks in front of the visitor. Epic stories are thereby understood as being retold across different eras and cultures. After five matches, the visitor can watch a chronological sequencing of all the examples within each archetype.

Tell a Story. The main plot points of the Perseus myth are extracted from the tapestry hanging in front of the visitor, who is then allowed to put them in any linear order to form a story arc within a comic book film. Within the comic book style, visitors can rearrange each narrative plot point within the cells of a typical comic book layout. They are then able to add thought and speech bubbles and add their own text or a provided sample. The visitor can then email to themselves the Perseus comic they created. Within the film style, the visitor sequences the plot points to select a soundtrack before watching their film in an animation.

Figure 14: Remix a tapestry into a comic book in the Tell a Story Lens. Photo courtesy of Local Projects

Globalism Lens

Global Influences. The visitor is presented with an artwork and asked to guess which two countries on the map influenced the artwork in question. An introductory animation explores the hybridity present within many artworks and design objects, thus calling attention to specific examples of cultural cross-pollination.

Create a Vase. Images and text introduce the vase trade between Europe and Asia. The visitor is able to make a vase by progressively building upon chosen options (shape, materials, patterns, and techniques), each of which is assigned a unique price estimate. The final product is showcased alongside a similar vase within the CMA collection to illustrate how techniques and origins affect the object’s market value.

Thirties’ Lens

Draw a Line. After a visitor draws a line across the screen, the interactive calls up and displays one of 442 artworks from CMA’s collection, which contains a similar line. All the artwork within this game was created in the 1930s and contains additional information. (This is an adaptation of the “Line and Shape” game located within Studio Play; see below.)

Explore the 1930s. What was the world like then?: A narrative montage of imagery from the 1930s depression era tells the story of the Great Depression and Cleveland’s role in this period. The information presented gives the visitor a context with which to approach the artwork in the lens and form a deeper understanding of how these artworks fit into the general themes of that era. The film is coupled with quotes from Cleveland artists and an accompanying soundtrack.

Painting Lens

Choose a Reason. The visitor is presented with a large image of an artwork from CMA’s collection (from a pool of 89 artworks in total) and asked to select one of five reasons they think the painting was created. Once selected, a visualization shows how other visitors in the museum voted, along with a short caption giving further information about that painting and the artist.

Make Your Mark. The visitor is presented with three abstract painting techniques, represented by different objects from CMA’s collection. The activity invites users to paint in the style of an abstract artist, exploring the techniques of pour, drip, and gesture as paint color palettes are generated from sample artworks. Visitors can contribute their painting to a collection of visitor-created art on view in the lens.

Figure 15: Understanding abstract painting styles in Gallery One’s painting lens. Photo courtesy of Local Projects

Remix Picasso. Introducing concepts of multiple and flattened perspective, and fragmented forms, the visitor is invited to rearrange abstracted elements or “pieces” of the composition in any way he or she likes, exploring the interplay between flatness and depth. The pieces may be manipulated through multi-touch zoom and rotate gestures.

Change Perspective. One-, two-, and three-point perspective is visually presented via animated, morphing perspectival overlays as they are applied to artworks within the collection. The visitor is then able to manipulate a three-dimensional shape, shifting perspective according to touch points across the horizon lines.

Discover Tempera. The tempera panel painting by Sano di Pietro directly in front of the visitor inspires a demonstration of the tempera process within the interactive. This visually captivating interactive shows each of the five stages of the tempera painting process at a zoomed-in scale. Each step in the process layers over another, and as a process is completed, the visitor is able to slide the next step over the last, seeing the highly detailed transition and effect of each stage in high resolution. Each stage has an accompanying process video as well.

Studio Play: Two interactives

The “Line and Shape” interactive is located in the Studio Play area of Gallery One and is oriented toward young visitors. Using multi-touch, it allows users to “draw” lines across a small wall (twelve Christie Microtiles) and matches those lines to those found within an artwork within CMA’s collection. The software searches through over 10,000 annotated lines within 7,000 of the museum’s artworks. From those lines and images, it chooses the artwork that includes a line that closely resembles the drawn line and composites the artwork under the drawing, so that the connection between the two becomes apparent. The application is written in C++ and uses the openFrameworks library. “Line and Shape” is unique in that it is the only exhibit running on the Apple OSX platform. This is the first exhibit in the world to use the Christie iKit on a MAC. The Line and Shape wall uses two linux computers to process the video across the twelve MicroTiles.

The “Sorting and Matching” interactive employs two 42-inch, 32-point multi-touch 1080p displays integrated into a custom table, with a narrow beam line array speaker to support audio cues for the youngest users. The displays are mounted back to back and share a housing. “Sorting and Matching” runs on two remotely located Windows 7 machines, and video and multi-touch is extended over Shielded Cat6 cable with digital extenders.

ArtLens: iPad application

The ArtLens iPad application is a unique personal guide for museum visitors. Loaded with video, audio, text, and still-image content, ArtLens helps visitors to explore the artworks on display in the galleries and encourages visitors to create their own customized tours. Visitors can check out an iPad preloaded with ArtLens upon entry to the museum, or bring their own iPad, and use the application both in Gallery One and throughout the museum. The application has five main features: “Near You Now,” “Tours,” “Today,” “Scanning,” and “Favorites” (indicated by a heart icon). The ArtLens iPad experience will sense a visitor’s location in the museum and offer digital stories about the surrounding artworks.

The size of the initial software download is ~25MB. On first start up, there is an additional download of data and featured image assets to ensure app responsiveness. The size of this initial package is ~400MB and generally takes about 5 minutes on site and 15 to 20 minutes off site, the latter depending on internet connection. Other image assets are downloaded on demand, with video assets being served via progressive download. All images are cached by the app, but video is not.

Near You Now: On site, the app integrates the museum’s Navizon service. This service, specifically installed for ArtLens, uses the nearest wireless access points to triangulate the device’s position. Using this indoor wayfinding technology, the visitor is alerted of nearby artworks featured on ArtLens. These “Featured Artworks” have interpretive media (including film, comparative images, text, and audio) and scanning image recognition functionality, and are featured within a tour or have related artworks associated with them for additional guided looking.

Scanning: The scanning feature incorporates the device’s camera and Qualcomm’s Vuforia image-recognition SDK to provide an augmented reality experience for users on site. When a user scans artwork marked with the ArtLens icon, the app will recognize the object and provide context-sensitive content about the work. This content is anchored within the app screen to the relevant regions of the physical artwork.

Tours: Visitors can select from both museum-curated and visitor-created thematic tours, with artwork locations specified on an interactive map that senses a visitor’s current position. Tours provide access to all interpretive media. Because the tours are directly linked to CMA’s Piction collection software, the museum can create new tours and additionally moderate visitor tours.

Today: This modular popup displays CMA’s daily schedule of events and exhibitions. The app ingests this content from the museum’s website via a RESTful web service.

Favorites: Visitors can favorite their preferred artworks to share via social media and can also create a personalized tour for other visitors to take, which will appear in both the iPad and Collection Wall.

5. Technology integral to design process

Our guiding philosophy for Gallery One was based on collaboration, teamwork, and an immersion in content to foster the best process of realizing an ambitious project in record time. Our interactive design firm, Local Projects, worked in deep collaboration with museum staff in multiple, extended group brainstorms to translate creative content into innovative visitor experiences. Many digital experiences were created and workshopped, and then the best were chosen for final execution. This helped offer flexibility to align the project budget and scope and timeline into a final approach that was optimized for each part of the team.

The team’s approach to the project, both in creative concept and technology, was driven by new interpretive research, CMA technology infrastructure, and by Local Projects’ extensive experience with interactive content development. The design development evolved during the wireframing phase. This approach was due primarily to the aggressive schedule required to complete this work. During the development of the wireframes, gaps in the current level of design details naturally emerged, requiring additional brainstorming and activity development. Once wireframes were complete, we moved into prototyping. The team believed this project required an accurate proof of concept of the interactive experience combined with hardware and systems support. Local Projects, Zenith Systems (AV integrator), and CMA’s IMTS team were able to deliver prototypes for the entire Gallery One team to test and improve upon.

In order for the technology to be built in tandem with hardware and while keeping the team in check regarding budget and technology feasibility, CMA hired an AV integrator to be involved in all steps of the process. In our research, we quickly understood that early coordination of the AV hardware and computer systems was a key factor in keeping the design on budget and schedule. Early participation of the AV integrator in the design phase allowed work with the architects as well as electrical and mechanical engineers to coordinate:

- Power requirements and locations and types of circuits

- Conduit specifications for AV systems. The AV conduit was installed with the electrical to reduce costs and duplication

- Heat loads were calculated early in the project to size heating, ventilation, and air conditioning for electronics that generate heat

- Coordination with the architect was critical to minimize the impact on the space of devices that generate noise

- Early coordination located the floor penetrations and ceiling devices to minimize impact on the space

- Early coordination on the mounting locations—especially for the MicroTile wall—was critical because of the tolerances of the wall being less than 1 millimeter of variation across the 40-foot-wide section

Most importantly, the coordination early in the design phase eliminated any change orders or changes to the space. As a result, infrastructure was installed in the right locations and there was always understanding of the technology that was going to be installed in the space. The locations of power, data, and technology infrastructure were planned for easy access for ongoing maintenance. This was essential for the Collection Wall. We were able to make it architecturally elegant and maintenance-friendly without compromising the design of the gallery.

We did benchmarking of other museums and exhibits that used technology, and talked to the people who maintain the spaces on a day-to-day basis to discover what worked well and what was problematic; that knowledge made the design of Gallery One better. By participating in the design phase for the physical space and art installations, we were able to create the software specification with a full understanding of the equipment that would be used and the technical support necessary. The final result was a combination of hardware and software that work very well together and are sustainable.

Modular design was important so that spare parts can be on site and all exhibits can be repaired on site in less than an hour. The hardware was also designed early on so that a software or hardware failure could be mitigated by having the exhibit perform in a limited way. Even if the actual interactive is not working, there can be engaging signage on the screen rather than a dark monitor. Remote IP-based power switches are also integrated into all of the devices to allow for remote reboot of any exhibit to restore it in the event of a software problem that requires reset of the touch interface or display.

CMA looked at a few different solutions for indoor wayfinding and selected the Navizon system since it offered the greatest flexibility to be retrofitted into an existing environment. The Navizon system uses a series of small nodes that create a meshed environment that allows the system to know where a visitor is located. Once the nodes were installed and calibrated in the galleries, our application developer could tap into the Navizon API so that its location data could be incorporated into the iPad app. CMA deployed Navizon’s Indoor Triangulation System (ITS): Over 100 Navizon ITS nodes were placed throughout the museum to locate, in real time, the iPads as visitors carry them through the museum. Even though the app is currently designed for iPad only, we chose this ITS because it tracks active Wi-Fi devices including Android, iPad, iPhone, laptops, and Wi-Fi tags with an accuracy of 2 or 3 meters, pinpointing floor and room. Though no application is actually required on the devices tracked by ITS, mobile apps like Artlens can leverage Navizon’s API and be aware of the device’s position anywhere throughout the monitored area. In addition, the ITS will enable CMA to measure Gallery One’s success via indicators such as dwell time versus time interacting with the iPad — i.e., we know how much time a visitor spends in a gallery and when they are interacting with the iPad screen.

Digitizing the collection

In 1996 the museum’s strategic plan outlined a commitment to becoming a national leader in the use of new and emerging technologies. A collections management database and digital scanners were purchased. By 1998, CMA was able to submit 1000 digital images with artwork metadata to the AMICO project. In 2003 CMA launched a massive expansion and renovation project which became an even greater force behind CMA’s image capture and inventory control. A dynamic inventory management module within the catalog database became a necessity, as the building project required the entire collection to be moved several times. At the same time, the initiatives to create digital assets for the collection for use in Collections Online received highest priority, as the administration saw the website as a way to continue to share the collection with visitors. As the collection was deinstalled and moved to storage, photographers were able to efficiently schedule large digital capture projects that would not be possible if the works were on view. Three photographers divided up the photography by type so that continuous steady progress is made across collections. CMA is well over 75% in its digital capture initiative and will have 100% digital capture within the next several months.

Importance of managing data dynamically

The images and data used in the Collection Wall and ArtLens are managed in a custom-built Piction CMS, built on Oracle 11g running on a Windows 2008 server. Object-related metadata is refreshed weekly from the museum’s collection management system in Piction DAM installations that support Collections Online and ArtLens, to ensure currency and synchronicity. Images for each object are transferred from the museum’s primary Piction DAM and post-processed to provide the 1.2 million image derivatives used to display artworks. The “cascading CMS” approach allows the Collection Wall and ArtLens to reflect current gallery installations (e.g., the art shown “moves” as it is moved within the museum, and “drops” when the object goes on tour/loan). Additionally, the Piction CMS allows hands-on management of over 500 video assets, 200 interpretive text assets, and more than 30 predefined tours, which can adjust over time to provide more and better interpretation to visitors. The Piction CMS runs on redundant hardware with solid-state drives to provide the best possible access performance for on-site visitors; a synchronized Amazon-based CDN provides images and videos for ArtLens users off site.

How the Collection Wall came together

The technical requirement for perfect black levels and precise touch interaction with multiple users was the starting place for research and testing of existing and emerging technologies to actualize the desired function of the Collection Wall. The displays were best solved by the use of the MicroTile, an LED-based rear-projection cube intended to be integrated as an architectural element. As a rear-projection emissive device, it has perfect black levels for showing art. These black levels could not be achieved with LED or LCD panels. The maintenance was addressed, as the half-life of the light engine of the MicroTile is 65,000,000 hours, and the tile can be rebuilt from the front removable screen.

The next challenge was the interaction. Ultimately the best solution was developed by a company called Baanto with a technology called “Shadow Sense.” They were in discussion with Christie MicroTile to make a version that would mount on the MicroTiles, and we started testing this technology over a year ago. The relationship with the manufactures provided us with development and prototype hardware to use while we developed the Collection Wall, and they finished the development of the touch hardware. When final development was completed in December 2012, CMA had the first and largest installation of this technology in the world. To complete the experience of the Collections Wall; there was a requirement to make the wall experience work with the iPad application that was also under development. Various interactive technologies were considered and tested, and ultimately RFID was chosen. The Collection Wall’s RFID server then communicates with the museum’s content management system and iPad application to create a dynamic and content rich experience for the visitor to Gallery One. Visitors using personal iPads receive a Gallery One sticker embedded with a unique RFID to attach to their devices. This ID is configured on the first Collections Wall interaction and automatically connects on all subsequent visits.

Making sure the content on the Collection Wall and the iPads is dynamic and maintainable was especially important to CMA. All information is pulled directly from our digital asset management systems. Therefore, any new accession or an object that has gone off view is immediately incorporated into the wall and iPad app. High-resolution digital cameras that range from 48 to 192 megapixels were used to photograph CMA’s objects. These provide us with museum catalog-quality photographs as large as 50 by 40 inches, and will enlarge on a standard iPad or computer monitor to 220 by 160 inches for examination of detail.

6. Conclusion: Next steps

The extended team is currently engaged in building a system of analytics within each of the interactives, to report desired data on visitor use. In addition, our audience research team is engaged in initial surveys of visitor preferences and preparing for an immersive study this spring, involving observations and intercept interviews with visitors. We are also planning for the next phases of the iPad app, with plans to deliver on new platforms, especially smart phones. We are particularly interested in extending the opportunity for visitor involvement in creating their own interpretation within the app. The Collection Wall will be leveraged as an enticement for major exhibitions, and a tool for gauging visitor interest in themes under development for permanent collection installation, exhibitions, and educational program development.

The groundbreaking program of interpretive technology that is now infused into the very bones of the CMA is garnering worldwide attention. We look forward to the opportunity to be in dialog with our peers at the Museums and the Web conference in April to report on early metrics and findings from audience research, to share our vision for future steps, and most importantly to hear feedback from our colleagues on Gallery One and the ArtLens app.

References

Adams, M., et al. (2009). Cleveland Museum of Art Permanent Collection Reinstallation Formative Evaluation Study. Unpublished 75-page report; PDF available through the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Falk, J. (2009). Identity and the museum visitor experience. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press.

Girardeau, C., C. Goeser, C. Olsen, N. Proctor, C. J. Reinier, & P. Samis. (2012). “Can Mobile Interpretation Also Be Social?” Session at the American Alliance of Museums Annual Conference, Minneapolis. Recording and PDF available for purchase at: http://www.prolibraries.com/aam/?select=session&sessionID=2269

Johnson, L., H. Witchey, R. Smith, A. Levine, & K. Haywood. (2010). The 2010 Horizon Report: Museum Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium.

Pitman, B., & E. Hairy. (2011). Ignite the power of art: Advancing visitor engagement in museums. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art Publications.

Rounds, J. (2006). “Doing identity work in museums.” Curator 49.2 (April), 133-50.

Schloder, J., M. Williams, & C. G. Mann. (1993). The visitor’s voice: Visitor studies in the Renaissance-Baroque Galleries of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art.

Cite as:

J. Alexander, J. Barton and C. Goeser, Transforming the Art Museum Experience: Gallery One. In Museums and the Web 2013, N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). Silver Spring, MD: Museums and the Web. Published February 5, 2013. Consulted .

https://mw2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/transforming-the-art-museum-experience-gallery-one-2/

2 thoughts on “Transforming the Art Museum Experience: Gallery One”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

What did it cost to create and install the interactives? We’re thinking of doing something similar with a MUCH small visitor center.

WOW! I am so impressed by this approach to the visitors first entry into the Cleveland Museum of Art. I have just accepted the Executive Director position at the Museum of the African Diaspora ( MoAD). This museum is a total of 20,000 square feet. Small, well, I like to think a little jewel. This approach to engaging the visitor would be crazy exciting for a tiny museum. I would like to find out more.

Great Job….Cheers,

Linda