In line, Online: Curator Buy-in Starting From The Ground Up

Eric Espig, Qatar, Alyssa McLeod, Canada

Abstract

How do museum Web content developers persuade curatorial staff to create and publish their own dynamic content online? Although on-site visitors to the museum interact with curators through the information provided in exhibitions and public programs, there has as of yet been little effort to extend that one-way interaction between curator and visitor to embrace the more conversational form of communication common to the Web. Most exchanges between curators and the public on the Internet are highly mediated by other museum staff responsible for Web content or learning. Michael Ames (2005) of the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia calls this act of anonymizing of the curatorial voice the “Wizard of Oz technique,” a communication style that implies the curator is a disembodied figure of authority with no front-facing public presence (p. 48). Several museums have attempted to encourage their curators to develop online content, mainly in the form of blogs, but as of yet there has been no systematic effort to develop a curator-specific platform to facilitate curatorial involvement online.

During the conceptual phase of a complete rebuild of their outdated website (launch date April 2013), staff members of the Communications Department at the Royal BC Museum decided to be the first to address this issue of curatorial anonymity head-on by democratizing content creation across the infrastructure of the museum. Specifically, Eric Espig, a Web specialist at the museum, and Alyssa McLeod, an intern and graduate student hired as a Web developer for the Web redevelopment project, dedicated a section of the new WordPress-powered website to curator content creation, a section made up of individual staff “profile pages” to allow curators and other interested museum staff members to showcase their research interests, work processes, museum-related hobbies, and unique personalities. These profiles highlight the work of the Royal BC Museum’s curatorial staff

Keywords: curator, wordpress, bootstrap, diy, website

Barriers to Curator-Created Content

But isn’t everyone a curator?

What is a curator and what do they do? The question of “curation” and what it actually means has been under much debate of late, particularly because the verb “to curate” has become almost ubiquitous in online communities. We “curate” our Facebook profiles, blogs, and Pinterest pinboards; Richard Lawson of the Atlantic Wire labeled “curate” as one of the worst words of 2012, deriding it as “a reappropriated term that…denotes a technique of cobbling together preexisting Web content and sharing it with readers/followers/whomever.” (as cited in Doll, 2012, para. 10) Once reserved for highly trained individuals working with specialized collection items, the act of curating information has become a personal expression of creativity. In an upcoming article on the relationship between curators and technology in the museum, Elaine Heumann Gurian attributes this democratization of online authority to the ease of access to information on the Web. Websites such as Wikipedia allow users to create, edit, and dispute scholarly interpretations, effectively creating what Gurian calls “internet competition” for curatorial authority (2013). Online projects like the GLAM-Wiki initiative (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums [http://outreach.wikimedia.org/wiki/GLAM]) have started to bring the curatorial voice of “cultural authority” (Russo, Watkins, Kelly, & Chan, 2008, p. 24) to existing online communities in an attempt to maintain cultural institutions’ involvement in public debate.

But how successful have museums been in broadcasting their curatorial voice to online scholarly communities through tools such as Twitter, Tumblr, and Pinterest? While facilitating an unconference session on open-source Web tools at the Museum Computer Network conference in Seattle in November 2012, we challenged other conference attendees via Twitter to create a list of curators with a strong online presence, whom we called “Rockstar Curators.” The suggestions were sparse, mostly consisting of references to a single website: Roger Launius of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s research blog on American history (http://launiusr.wordpress.com/).

There are, of course, a number of other notable museum resources readily available to the public online: the aforementioned GLAM-Wiki initiative, Nina Simon’s ever-relevant Museum 2.0 (http://museumtwo.blogspot.ca/), and museum blogs that feature guest posts by curators, such as that of the British Museum (http://blog.britishmuseum.org/). Still, these results are disappointing when compared to the strong online presence of members of similar public knowledge institutions. In certain academic disciplines Twitter and blogging have developed as a parallel peer review system where scholars can test research ideas and share them with each other and the general public. (See, for example, CommentPress, an open-source WordPress Plugin the Institute for the Future of the Book developed to facilitate online peer review [http://www.futureofthebook.org/commentpress/].)

Museum web content creators have despaired for some time now in their efforts to encourage curators (and, indeed, the rest of museum staff) to contribute content online. We contend, however, that this issue of content creation is not simply a matter of adding an extra task to the curatorial workload, which is already quite laden; it is a question of understanding how the entire museum relates to the public, and understanding in turn what the public expects from the museum. The museum of the twenty-first century does not simply follow the Enlightenment model of informing the public about collection items. The new museum facilitates dialogue among its visitors, a sea change in identity Russo et al. (2008) summarize succinctly: “Museums are now sites in which knowledge, memory, and history are examined, rather than places where cultural authority is asserted.” (p. 22) Indeed, focus group testing of our old website in the summer of 2012 indicated that 80% of visitors wanted to see more contextual information about collections items online.

This difference in the way museums engage with the public is the reason why the Royal BC Museum’s curator profiles project has embraced a multiplicity of content creators from across the museum infrastructure. We are attempting to accomplish what Stephen E. Weil famously proposed museums do in 1999: that is, to be “for somebody” (and by somebody) instead of “about something.” (p. 229) A 2006 study confirmed that approximately 89% of museum visitors prefer exhibitions that allow them to comment on the topics being presented, particularly when those topics are controversial or culturally relevant. (Kelly) Christiansen (2009) suggests that one of the functions of the museum is to create “spaces for contemplation where individuals can have a personal and meaningful response to the great legacy of the past.” Many museums have attempted to create this forum for debate through social media: British Columbia’s Maritime Museum, for example, is hosting a Tsunami Debris Project (https://www.facebook.com/TsunamiDebrisProjectMaritimeMusBC) in which members of the public can upload and map pieces of debris washed up on Canada’s shore from the 2011 tsunami in Japan, and many other museums have “crowdsourced” entire exhibits via online tools (the Walters Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Walker Art Center, to name a few). But at the Royal BC Museum, we are taking a different approach by connecting museum visitors to museum staff in a highly personal way.

What’s the point in changing anything?

Like many other museums and galleries, the Royal BC Museum has faced challenges when it comes to curator-created online content. Until the launch of our new website in the spring of 2013, our museum’s website was about seven years old, featuring an infrequently updated blog populated mainly with entries written by archivists and staff from the Learning Department. There was no significant public-facing Web presence for museum staff in general, and our curators in particular, even on our website’s official staff pages. Espig was hired in 2011 to manage the museum’s online presence on the website, Twitter and Facebook systematically, instigating a course of public engagement that started in the Royal BC Museum’s Communications Department and eventually moved through the rest of the museum.

With the 2012 appointment of a new director, Professor Jack Lohman of the Museum of London, the Royal BC Museum’s new strategic priorities included four types of work: improving visitors’ on-site experience; strengthening our digital infrastructure; creating better access to our collections, archives and learning; and aligning our skills with our forward plan. The curator profiles project constitutes an attempt to move these four work types into the digital sphere while simultaneously building up a community of museum followers in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, and the world. Based on conversations with curators, staff members, and the executive committee of the Royal BC Museum, we identified two key institutional barriers that have come up in our attempt to display curator- and staff-created content online.

1. Anxiety over change

Due in part to the slow-changing nature of museum work, there is some anxiety about change in workflow in the Royal BC Museum. This is largely related to the perceived threat of an increased workload, understandable for staff who are often tasked with a wide variety of duties in their current positions. We found that many staff members viewed social media interactions like tweeting as the equivalent of e-mail correspondence; they believed that, since they get so many questions via e-mail per day, a social media presence would multiply those inquiries exponentially, making response difficult. Many of these suspicions came from unfamiliarity with what social media actually is, and what role it has already played in communities that have embraced these platforms of communication, including academic groups. One department head asked us to estimate how many minutes per week his staff would have to devote to updating their profiles in relation to how much money the profiles would earn through donations and on-site visits to the museum – an understandable concern for a department faced with learning a set of new skills.

The jargon-like nature of the language used in online communication did not help alleviate these fears. Colin Beardon and Suzette Worden (1997) stress the importance of using familiar vocabulary in museum correspondence of all types:

The medium should not impose a uniform structure of knowledge upon users but should enable humans to exchange knowledges in ways that are natural to them. If we want users to create texts in which the meaning is open, then the language of communication must not force closure. (p. 70)

We were faced with the task of making WordPress, Twitter, and blogging seem like “natural” forms of communication to museum staff who were not necessarily comfortable with any form of digital engagement beyond e-mail.

2, Anxiety over open access.

“Open Access to Knowledge,” a philosophy embraced by many universities and cultural institutions across the world in the Berlin Declaration of Open Access to Knowledge in 2003, is the practice of providing unrestricted access to scholarly information online to the general public. This suspicion of open access relates in part to conflicting understandings of what role the museum ought to play in the public sphere: a supplier of authoritative knowledge or a facilitator of education. Moreover, especially for museum curators whose careers often depend on their publishing histories, public accessibility can seem to threaten the scholarly value of their research. Many curators and archivists told us they were afraid of posting their research online in case a reader were to steal it or a peer-reviewed journal refuse to publish the results of that research elsewhere. Museum websites are not peer reviewed, so, some staff concluded, there is little professional value in publishing to a public audience in a museum blog. Many staff members concluded that few non-professionals would even be interested in their research in the first place.

A related concern in our Human History Department was the sensitive nature of some of the museum’s artifacts. First Peoples tools, art, and cultural objects comprise about a third of the Royal BC Museum’s collections. What if, one curator asked us, we are blamed for offensive or controversial things said in public debate on Twitter? The general attitude was that if we facilitate public conversation about our collections items, that conversation will necessarily be negative. We were faced with the task of creating “radical trust” for our museum visitors, on-site and offline (Spadaccini & Chan, 2007, para. 40), believing that the Royal BC Museum’s online community would be supportive of our efforts as an organization and that museums ought to facilitate public dialogue about controversial issues.

We will now overview the steps we took to address these concerns at the Royal BC Museum: first, the way we dealt with institutional anxiety over change, and then, how we addressed anxiety over open access.

Creating Buy-In

I don’t want to tell people what I had for breakfast.

Before introducing new Web technology into the work environment at the Royal BC Museum, we stepped back to assess any pre-formed opinions and prejudices staff possessed against that technology. For some employees, Web jargon came loaded with unpleasant associations. We decided to create a new taxonomy of Internet terms for the curator profiles to get past some of the baggage that can come with that terminology. Although Twitter can be an invaluable communication channel for curators to talk to the public and to each other, its unfortunately onomatopoeic name “Twitter” and all of its derivatives (“tweet,” for example) can minimize its value. We decided to avoid the name “Twitter” to keep our conversation with museum staff from drifting into a pedantic debate about usefulness and audience, known now at our institution as the “I don’t want to tell people what I had for breakfast” defense – a common stereotype about the supposedly banal nature of all social media content.

Even longer established and generally accepted terms like “blog” and its derivatives can cause problems. Two curators on separate occasions argued that they would never blog because it was too much of a time commitment. When asked why, each explained that a successful blog would obviously have to be updated frequently to maintain audience interest.

Beyond dispelling misinformation, introducing a new taxonomy of Web terms also helped create a freshness to the project, a sense of control and a collective proprietary feeling over what our museum was accomplishing. The following is a list of some of the problematic terms we encountered and the replacement terms we used in their stead.

| Loaded Term | Replacement Term |

| Twitter / Social Media | New Communication Channel |

| Twitter Feed | Dropbox / Bulletin Board |

| Blog | Profile Page |

| Macro-blog (aggregate blog) | Online Magazine |

| Blogging | Authoring / Publishing |

| Blogger | Author / Web Author /Publisher |

| Staff Profile Page | Hockey Card |

Table 1: A new taxonomy of Web terms

Everyone loves this idea!

Had we solely focused on the curators in our attempt to get them to buy in to the idea of authoring their own Web content, we would have almost certainly run into a unified front of resistance. Instead, we grouped all of the curators together with collection managers, archivists, conservators, programmers, exhibit technologists, designers, and department managers, and in the initial stages we successfully presented our project as open to all interested staff members throughout the museum. Key to this success was approaching those who manage the curators and identifying among them the most enthusiastic towards the idea of staff-authored Web content. When we identified Kelly Sendall, the manager of the natural history department and its six curators, as a strong supporter of the idea, we used him as a “poster child” for a sample profile to help explain our project while simultaneously demonstrating that the person the curators ultimately report to has already “bought in”. Indeed, there was a quick and positive buy-in from his department once this sample profile was created.

Look at five people around you. Four of them will be authoring Web content by the end of the year.

Continual reassurance, listening and projected confidence help foster the trust needed to get people to buy into changes to workflow that come with developing Web content, however slight those changes may seem to a regular user of social media. An important milestone in our project was getting the forty or so interested museum staff together at the same time in a general information session about the project. We told them the purpose of the session was to inform them how the project would progress and what their next steps would have to be. Regardless of individual technological ability, we treated all participants as if they had no experience authoring for Web or with any type of social media. As people started to air their private concerns about the project, they were also expressing the fear and concern their colleagues shared. Often staff members helped alleviate each other’s fears; many who shared the same concerns realized how unfounded these concerns were when they were discussed in a group setting. We left this particular meeting noting an overall positive feeling among museum staff members about the project, with a sense of trust that this project could succeed.

Providing web training in the form of monthly drop-in workshops with topics such as “smartphone photography,” “Twitter use,” or “WordPress authoring” also alleviated many fears surrounding new technology. We also guaranteed participants one-on-one opportunities to address any complex problems they may be having. Finally, we integrated a series of instructions for simple tasks such as “How to upload a photo,” “How to write and publish a post,” “How to compose a Tweet” into the backend of the profile pages so they could be consulted as needed. This was part of a conscious effort to mitigate some participants’ perception that maintaining their individual profile page would be technologically complex.

We attempted to convey to the group that the project was allowed to fail, as were their contributions. The staff profiles project is an experiment in democratizing content creation, and its results will prove valuable whether they bring failure or success. Our answer to some of the more extreme scenarios posited – “What if I have too much work to do?” “What if someone posts something offensive and the museum is blamed?” – was simply that, if these profiles do not work, we will adjust them.

Now I can save the Olympia Oysters!

Self-interest, competitiveness with peers, and the allures of additional research money and public attention for pet projects are powerful motivators to encourage museum staff involvement on the Internet. Many staff members at the Royal BC Museum felt that their work was not sufficiently represented or appreciated, particularly in the areas of conservation, research, and archives. Touting the profile pages as a vehicle to raise awareness of the individual efforts of staff members was a successful approach to getting participants to feel a sense of ownership over their individual pages, encouraging them to attach a real, personalized value to sharing content online. The profile pages could be used to raise money for certain projects, create a professional online presence, or to develop new and urgently needed Web authoring skills to keep up with professionals in other fields. The profiles are, in essence, vanity projects: a fun and acceptable way to show off work staff members are proud of, distribute information the public does not know “but absolutely should.” One of our curators has taken on the task of single-handedly raising awareness of the rarely-discussed Olympia Oysters; another threatens to post his PlayStation ID on his profile so he can play online games with museum visitors; and a conservator looks forward to show off the beautiful handmade dolls she carves from locally-sourced British Columbia wood.

Not much, just a pilot project I have on the go.

The culture of museum project management, particularly in an institution such as the Royal BC Museum, an arm’s-length corporation of the Government of the Province of British Columbia in Canada, can be overly focussed on bureaucracy, planning and assessment at times when creativity, experimentation and innovation are needed. The relatively fast moving landscape of the Web does not fit well with a traditional model of museum project, exhibition or program development. We found that using another taxonomic device, “pilot project,” is a very helpful way of encouraging curators to excuse shortcuts to normal museum policies and procedure. Even more importantly, the term helped alleviate some of staff members’ fear of the consequences of open access learning. Participants in a pilot project can make mistakes, change their minds, modify the kind of material they post, or even back out if need be. This project also existed under the guise of “pilot project” when presented to the museum executive committee as it was piggybacked onto the more closely managed redevelopment of a new website for the museum created in parallel by Espig and McLeod.

The Result

I’ll trade you the Sedin Twins for two Human History curators.

Cost, usability and support were the three main criteria when choosing the platform on which to build the curators’ profiles. The Royal BC Museum had already relied on the open-source and (in 2012) ubiquitous content management system (CMS) WordPress to create and manage various microsites, and the Communications Department had already selected it as the CMS for the new Royal BC Museum website. Moreover, WordPress’s online community provides free support for everything from basic usability questions to more complex Web development issues. It was a simple decision to extend the WordPress install for the new website to include the profile pages.

We purposefully designed the profile page template so that the content would not appear stale even on infrequently updated profiles. Each profile includes a professionally photographed “profile pic,” also affectionately known as a “hockey card,” and seven content areas available for the author to add to or edit. The “hockey card” idea was initially developed to pitch the concept of the profiles to prospective participants: we wanted museum staff to feel as if they were members of a team with the public appeal of famous athletes. But the concept proved so popular it found its way into the design, extending to the Graphic User Interface (GUI) on the homepage of the collected profiles. We implemented an interactive, animated filter called Isotope (http://isotope.metafizzy.co/index.html), a jQuery plugin that allows the user to re-order and sort block elements on command. Isotope’s animated movement introduces an element of fun to the process of browsing the staff profiles, mimicking the way a hockey card collector might shuffle through his or her collection.

Figure 1: Profile Picture of

Kelly Sendall, Head of Collections

Care & Conservation

The hockey card staff portraits create a uniformity and aesthetic that allowed us to colour code and divide museum staff into six “teams” with corresponding logos:

Figure 2: Logos for Natural History, Human History

and Archives

The profiles can be sorted by the following options: department, expertise, job, recent updates, popularity, and name. This graphical user interface creates a “wow factor,” giving our authors a sense of pride in being involved in the project, and of course attracting visitors to the website post-launch.

The seven content areas on each profile are:

1. Bio: A brief blurb about each staff member that details their education, background, and areas of interest. These introductions were generally written by the individual staff member or, in some cases, taken from existing copy written by an employee in the Communications Department.

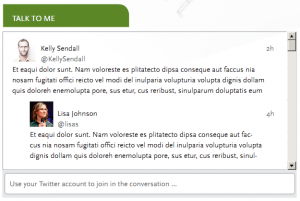

2. Talk to me: An embedded Twitter timeline with the Twitter branding masked from view.

Figure 3: Design draft rendering of the “Talk to Me” section.

Figure 3: Design draft rendering of the “Talk to Me” section.

This timeline allows us to remove the loaded terminology of Twitter, letting both authors and readers compose messages directly from the profile page in question. This masking of Twitter’s branding helped alleviate staff concerns that Twitter would seem unprofessional. We aimed to take advantage of the conversational benefits of social media without placing pressure on our curators and other staff members to build up a large number of followers.

3. My Downloads: A series of links to author-selected files such as PDFs of previous publications whose copyright allows for online display. We provided style guides to ensure consistency in formatting PDF files. Giving the curators control of what information remained “open access” helped address many concerns about making scholarly research publically available.

4. My Posts: Traditional blog posts with no visible dates, organized by most recent to oldest. For the purposes of these profile pages, a post must be at least one paragraph long and contain at least one image.

5. My Recommended Links: A list of links to external websites of interest, part of our attempt to acknowledge museum visitors’ ability to seek authoritative information elsewhere.

6. Image Gallery: A collection of author-organized photo albums. These include existing images of the museum collection, digitized archival records, photos of events, and personal snapshots. We have encouraged staff members with smartphones to make use of free online services such as Instagram to create attractive, low-maintenance shots they can easily share online.

7. Video: Videos of the author or chosen by the author. Like photos, videos are now more easily produced by individual staff members because the museum is transitioning from staff landlines to smartphones.

In all cases save one, these categories reflect the content typically produced in the museum. The exception, the “Recommended Links” section, was added to meet a desire on the part of curators to promote external like-minded organizations or raise awareness of others’ work when needed.

New content from each staff member’s profile is also pushed out into a “macro-blog” accessible in one place for easy access. The end user reads the macro-blog as they would any other multi-authored blog. Highlights from this content are then pushed out by RSS feed into a weekly iPhone publication available on Newsstand, the Royal BC Museum “Curious Magazine.” Our goal is to bring the research and educational values of the Royal BC Museum right into our visitors’ hands, an initiative our institution undertook in August 2012 with the launch of Wifarer: a mobile app we created with a Victoria-based tech startup that acts as a virtual tour guide of our collections.

Figure 4: Design draft of complete curator profile page

Conclusion

The staff profiles project at the Royal BC Museum takes part of what curators do – disseminate information – and disperses it across the museum infrastructure. Curators maintain their authoritative relationship with the museum’s collection, of course, but our project attempts to highlight other important areas of knowledge at the museum: public programs, exhibition building, archiving, etc. Education, we argue, ought to be part of everyone’s role in the museum, from a newly hired intern to the CEO. Weil (1999) suggests that public education is in fact a museum’s ethical responsibility: if an institution receives public funding, whether in the form of government grants or even tax breaks, they ought to provide public support. For Weil, our criteria for determining a museum’s success should include how much it impacts its visitors and surrounding community: “If our museums are not being operated with the ultimate goal of improving the quality of people’s lives,” he concludes, “on what [other] basis might we possibly ask for public support?” (p. 242)

The benefit of a pilot project is that it can easily adapt to changing circumstances without being considered a “failure.” The first step of our task was to encourage the curators and other staff members to develop “radical trust” for museum visitors; the second step of our task is to in turn develop for ourselves a “radical trust” in the discretion of staff members who are creating online content. Our “buy-in” process resulted in a set of highly individualized profiles that are effectually “curated” by staff members personally invested in the profiles’ success.

Although it is too early in this project’s development to determine all its ramifications, we propose that this staff profiles project will change the way staff members at the Royal BC Museum interact with the public online and offline. As Russo et al. (2008) have already contended, an institution’s involvement with what they call “participatory communication” relates to its very organizational structure. (p. 25) By giving a broad variety of staff members the same task – that is, creating and sharing content online – we are effectually bringing all participants to the same level regardless of their status within the museum. Our photographers will blog alongside our curators, and our Learning Department staff will tweet alongside our archivists, potentially even responding to each other’s work. According to our CEO, Professor Jack Lohman (2012), museums should act as “cultural mash-ups,” that is, institutions that “collaborate with other cultures so much the word [collaboration] disappears.” The profiles continue this task by “mashing up” the museum itself, turning the relationship between staff and public (and between staff and staff) on its head.

Acknowledgements

For their advice, guidance, and support over the course of this project, we would like to extend our special thanks to Jack Lohman, David Alexander, Jim Olson (http://www.ha5bro.com/), and all of the curators and staff members at the Royal BC Museum who were willing to be our guinea pigs.

References

Ames, M. (2005). “Museology Interrupted.” Museum International 57, 44-51.

Beardon, C. & S. Worden (1997). “The Virtual Curator: Multimedia Technologies and the Roles of Museums.” In E. Barrett & M. Redmond’s Contextual Media: Multimedia and Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 63-86.

Berlin Declaration (2003). Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities. Berlin. Retrieved January 2, 2013, fromhttp://oa.mpg.de/lang/en-uk/berlin-prozess/berliner-erklarung/.

Christiansen, K. (2009, June 18). The Role of the Museum Curator. Retrieved December 28, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_u7F_4xu75s.

Doll, J. (2012, December 18). “An A-to-Z Guide to 2012’s Worst Words.” The Atlantic Wire. Retrieved December 19, 2012, from http://www.theatlanticwire.com/entertainment/2012/12/worst-words-2012/59909/.

Gurian, E. H. (2012). “The Curator’s Next Choice.” Unpublished manuscript.

Kelly, L. (2006). “Museums as Sources of Information and Learning: The decision making process.” Open Museum Journal 8. Retrieved January 2, 2013, from http://hosting.collectionsaustralia.net/omj/vol8/pdfs/kelly-paper.pdf.

Lohman, Jack. Keynote Address. Speech presented at the British Columbia Museums Association Conference, Kamloops, BC. October 2012.

Russo, A., J. Watkins, L. Kelly & S. Chan (2008). “Participatory Communication with Social Media.” Curator 51(1), 21-31.

Spadaccini, J. and C. Sebastian (2007). “Radical Trust: The State of the Museum Blogosphere.” Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Retrieved January 2, 2013, from http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/spadaccini/spadaccini.html.

Weil, S. E. (1999). “From Being about Something to Being for Somebody: The Ongoing Transformation of the American Museum.” Daedalus 128(3), 229-58.

Cite as:

E. Espig and A. McLeod, In line, Online: Curator Buy-in Starting From The Ground Up. In Museums and the Web 2013, N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). Silver Spring, MD: Museums and the Web. Published February 25, 2013. Consulted .

https://mw2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/in-line-online-curator-buy-in-starting-from-the-ground-up/